The endless search for a crypto use case

Are we there yet?

Today I read a Nat Eliason post titled “Does Crypto Have Any Good Use Cases?”1

I don’t want to pick on Nat. In fact, I have called his prior crypto writing “essential reading,” precisely because he has been instrumental in helping me understand crypto better by writing about key elements of it in admirably clear terms.

But his latest piece here is a good example of the sort of magical thinking that pervades the crypto ecosystem. I’m using his piece as an example because Nat is a smart guy and cannot be reasonably painted as someone who doesn’t understand crypto or hasn’t thought much about how it all works.

Indeed, one of the strangest aspects of crypto is the seemingly endless ability of many intelligent participants — and Nat is just one example among many here — to confidently state things that are straightforwardly incorrect and/or trivial to rebut with about 10 seconds of googling. Unfortunately, this piece is no exception.

The below commentary will be easier to follow if you read his post first.

Claim #1: “Crypto is EARLY. Painfully early.”

I’ve covered this in detail previously, so I won’t do it all over again here, but this claim is just empirically false. Satoshi Nakamoto’s Bitcoin whitepaper was published in 2008. Even if you’re being extremely generous and allow boosters to define the crypto era as beginning only with the release of the Ethereum whitepaper in 2014, that still means we’re closing in on a decade since the birth of the ecosystem, with nary a mainstream use case to show for it other than drugs and ransomware.

Weirdly, Eliason favorably compares the evolution of the crypto space to the mobile revolution. But as I have written previously, the pace of innovation on mobile — and specifically the explosion of apps following the debut of the iOS App Store in the same year as the Bitcoin whitepaper — puts crypto to shame.

Large swathes of activity in modern life — calling an Uber, booking a trip on Airbnb, using Google Maps to get around a city, messaging friends and family around the world on WhatsApp, listening to podcasts, checking your email, and a nearly infinite array of other tasks you do regularly — are made possible by the App Store ecosystem.

In crypto, on the other hand, you can speculate on shitcoins and make bets in DeFi, and that’s about it. To the extent that the crypto space intersects with the real world, it’s primarily via the endless parade of multimillion dollar hacks — here’s a $200 million one from just yesterday — that immediately get laundered out through mixers like Tornado Cash and then presumably cashed out into fiat currency so it can actually be used in the real world.

The App Store isn’t early. Neither is crypto.

Claim #2: Crypto prevents government censorship and property seizure

Eliason argues that Bitcoin was the first “global, digital, trustless, hard monetary asset” and writes that, while gold ETFs are somewhat similar, “you’re still trusting some other institution to redeem that ETF, and the government or bank could easily seize it or restrict your access to it.”

Along similar lines, he also compares property rights on the blockchain to what exists today:

Domain names can be taken away by ICANN. This blog could get taken down by Substack. Your Twitter account could be taken down. Your Instagram photos could get wiped out.

You can only rent on the pre-blockchain Internet. But with code that can live everywhere forever, without needing a trusted third party to support it, you can own things in a way that’s arguably even better than Title rights in a developed nation. You do still rent your real estate from the government, after all.

Right now, digital ownership is focused on art, pictures of monkeys, and ENS domains. But if you looked at the Lightsaber and Beer-pouring apps on the 2009 iPhone and said, “see, apps are all silly!” then you would have been missing the point. We don’t really know what all will get done with digital property rights, but the fact that we have them for the first time is pretty exciting.

Much of this section is either flat-out wrong or highly misleading.

First (and more related to Claim #1 above), no one would have looked at the 2009 iPhone and concluded that the Lightsaber and Beer-pouring apps demonstrated the device’s lack of utility. The Facebook iOS app was released in 2008! Indeed, among the top iOS apps for 2009 were The Sims 3, Madden NFL 10, and MLB.com At Bat. This is one of those maddening “please just use Google” moments that are so common to the “crypto is still early” crowd.

But another one of the prevailing implicit myths of the cryptocurrency space — and the centerpiece of Claim #2 — is that crypto somehow manages to avoid the external dependencies that dominate the rest of society.

Gold ETFs, as Eliason notes, are subject to government seizure, Twitter and Substack accounts can be banned, and so on.

That part is actually true. But many, many centralized choke points exist in crypto as well.

Signal founder Moxie Marlinspike’s January post “My first impressions of web3” memorably demonstrated two gaping holes in crypto’s decentralized armor. First, because no consumer-facing device — especially a mobile phone — has the digital storage capacity required to operate its own Ethereum node, the vast majority of consumer interactions with Ethereum are intermediated via centralized blockchain API providers like Infura, which query the state of the blockchain on apps’ behalf. “Imagine if every time you interacted with a website in Chrome, your request first went to Google before being routed to the destination and back,” Marlinspike writes. “That’s the situation with ethereum today.”

A separate but related centralization vulnerability applies to nonfungible tokens (NFTs) listed on platforms like OpenSea. Marlinspike created an NFT whose image changed based on the requester’s IP address and/or user agent, as a demonstration of the fact that owning an NFT doesn’t protect you from having the underlying asset changed or even removed at any time. It’s like buying the deed to a property and then showing up to check it out, only to discover that the entire house has been demolished and replaced with a giant 💩 emoji.

Inexplicably, OpenSea took down his NFT, implying (but not stating) he had violated its Terms of Service. But more strangely, the NFT didn’t just disappear from OpenSea: it also disappeared from his non-custodial crypto wallet itself. How is this possible, if NFTs live on the uncensorable blockchain? Well, it turns out MetaMask uses OpenSea’s APIs to find NFTs, so when OpenSea — a standard, centralized company — bans an NFT, that NFT also disappears from non-custodial, theoretically decentralized, and uncensorable wallets like MetaMask.

Marlinspike concludes:

Given the history of why web1 became web2, what seems strange to me about web3 is that technologies like ethereum have been built with many of the same implicit trappings as web1. To make these technologies usable, the space is consolidating around… platforms. Again. People who will run servers for you, and iterate on the new functionality that emerges. Infura, OpenSea, Coinbase, Etherscan.

There are other choke points as well. For example, the two largest stablecoins — USDC and Tether, with a collective capitalization of $120 billion — both maintain address block lists. That is, they can, and do, freeze assets denominated in their respective stablecoin tokens such that they cannot be traded or spent.

More to the point, both Tether and USDC have frozen these funds specifically at the request of law enforcement:

"Tether routinely assists law enforcement in their investigations... Through the freeze address feature, Tether has been able to help users and exchanges to save and recover tens of millions of dollars stolen from them by hackers," said Hoegner.

Tether's development came to light after The Block first reported that CENTRE, which issues the USDC stablecoin, blacklisted an Ethereum address holding 100,000 USDC for the first time.

A CENTRE spokesperson said that the consortium, managed by Circle and Coinbase, blacklisted the address "in response to a request from law enforcement."

This gets at a fundamental and inherently unsolvable weakness of the entire crypto ecosystem, which is that on- and off-ramps to fiat currencies are colossal choke points that governments routinely and effectively exploit to set boundaries on what is and isn’t allowed within the crypto space.

Take Binance, for example. The world’s largest crypto exchange, Binance has long enjoyed a reputation as a sort of regulatory wild child, facilitating billions of dollars of financial crimes, bouncing vaguely between various jurisdictions — its founder, CZ, is still cagey about where its headquarters is located — and acting as if it’s not subject to any particular country’s laws.

And yet late last month, as part of a Coinbase insider trading case, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) fired a warning shot across the bow, listing nine crypto tokens that it considered to be unregistered (and therefore illegally listed) securities on Coinbase. Within days, Binance’s US arm (Binance.US) announced it would de-list the only one of those nine (the AMP token) it supported on its platform, explicitly naming the SEC document as the impetus:

We operate in a rapidly evolving industry and our listing and delisting processes are designed to be responsive to market and regulatory developments. Last week, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) filed securities fraud charges against a former employee of Coinbase, among others. In its suit, the SEC named nine digital assets that it alleges are securities. Of those nine tokens, only Amp (AMP) is listed on the Binance.US platform.

Out of an abundance of caution, we have decided to delist the AMP token from Binance.US, effective August 15, 2022. While trading of AMP may resume at some point in the future on the Binance.US platform, we are taking this step now until more clarity exists around the classification of AMP.

It is important to note that this incredibly powerful governmental leverage applies to every crypto company that allows users to deposit U.S. dollars (or euros, or yen) and/or withdraw to those same currencies, because enabling these features puts those companies directly in the crosshairs of law enforcement and regulation authorities who are tasked with ensuring that Know Your Customer (KYC) and Anti-Money Laundering (AML) checks are being carried out by all financial platforms, whether they’re traditional financial entities like Bank of America and Charles Schwab or crypto exchanges like Coinbase and Binance.US.

And unfortunately for the crypto-is-uncensorable crowd, virtually no one actually wants to keep their financial assets in crypto in the long term. This is because:

prices are both heavily manipulated and absurdly volatile

even the “safe” crypto assets — the stablecoin tokens that comprise a large percentage of total crypto holdings — are suspiciously secretive about their finances despite operating a theoretically very simple business model

you can’t use crypto to do just about anything useful and legal in the real world

Taken altogether, here’s what that means: end users always want a way to get money out of crypto and back into fiat currency. And this desire hands governments all the tools they need to starve the crypto ecosystem at will, by cutting off access to inflows and outflows if participants don’t follow the rules. When a reasonably competent and powerful government cares enough about stopping something from happening, it is very difficult, if not impossible, to continue doing business as usual.2 And this reality continues to take the hand-wavily libertarian crowd of crypto enthusiasts by surprise.

The persistent requirement for fiat on- and off-ramps is why virtually every anti-censorship technique that crypto comes up with instantly suffers from the same Achilles heel.

For example, cybercriminals use crypto mixer services like Tornado Cash, which blends together multiple transactions to prevent external observers from tying withdrawals to their associated deposits. But even leaving aside Tornado’s technical vulnerabilities that can compromise its users’ anonymity, the U.S. government could set rules prohibiting fiat-enabled exchanges from handling any funds that have interacted with a Tornado address.

(Note: Six days after this post was published, the U.S. Treasury Department did in fact sanction Tornado Cash. Needless to say, I had no advance or inside information about any of this.)

The cryptocurrency universe is like a privately run interstate highway system: the roads are wide and everything moves quickly3, but if all of the entrances and exits are guarded by cops, it doesn’t really matter how wide or efficient the highway is because the highway operator will still need to accommodate whatever the cops want in order to get any traffic in or out.

On that note, I really want to hone in again on Nat’s point below, which is a widely held crypto belief:

You can only rent on the pre-blockchain Internet. But with code that can live everywhere forever, without needing a trusted third party to support it, you can own things in a way that’s arguably even better than Title rights in a developed nation. You do still rent your real estate from the government, after all.

The persistent fallacy that blockchains and NFTs protect property rights in a more secure way than existing mechanisms demonstrates something important about many crypto boosters: they understand code4, but they are absolutely clueless about power.

Property rights are only abstract until they aren’t. If a homeowner arrives at his house at the end of the workday and finds someone squatting in his living room and claiming they own his property, he’s going to call the police. And if it’s not immediately clear to the police which person actually owns it, they can check the property records against each claimant’s identity in order to figure it out. At which point, cops — that is, armed agents of a very centralized state — will forcibly evict whoever’s lying.

At its most basic level, that’s what property rights are: the fact that a specific group of people with weapons will ensure you get to keep the thing that government records say you own. And this means that the most important question in this entire scenario is which property records these armed people consult.

This is why, whenever you read about a solution involving property rights — and especially physical property rights, such as real estate — being put on the blockchain, you should be immediately skeptical. If you turn your house into an NFT on the blockchain and sell it to someone else, and that person shows up to the house only to find someone else living there, the cops aren’t going to check the blockchain. They’re going to check the property records at the courthouse.

Those records could be memorialized in a physical logbook, stored in an MS Access database from the 1990s, or handwritten on a stack of Denny’s napkins. They could even be on a blockchain! But the chosen method of storage is simply a red herring: the salient point is that you have to rely on the centralized government to protect your rights.

There are no blockchain police. The mere presence or provenance of metadata on an open ledger has no bearing on whether armed agents of the state will actually ensure you get to keep your Bored Ape.

Claim #3: Single sign-on (SSO) using wallets is superior to existing solutions

Eliason writes:

Web2 companies like Facebook and Google have tried to make single-sign-on a thing for years. It started to get popular maybe five or six years ago, then everyone realized that if they shut down their Facebook or Google account, they would lose access to everything, and it started to wane.

But crypto applications are natively single-sign-on since you don’t typically create an account, you just connect your wallet. This is such a different experience that you’ll need to just try it to understand it, but it is a much nicer way of having an account on a website without having to give them a way to spam you.

There are some important differences between SSO using Google or Facebook and doing it via an Ethereum wallet.

One is that, in crypto, there is no easy backup plan if you lose your private key: once the key is gone, you’ve now lost your ability to log on to all of the services where you use that wallet. Think about how many times you’ve clicked on a “Forgot your password” link and now try to imagine not only not having that option, but also that instead of just forgetting your password to a single service, you’ve now been permanently and irreversibly locked out of every account you use online: email, social networking, your own banking and investment accounts, you name it. Gone. This is the promise of universal SSO using wallets.

Now wait a minute, some will say. This isn’t entirely true: you can set up a “multisig” wallet, which is a type of wallet that can be accessed using a combination of people rather than by a single person alone. For example, you can set up a 2-of-3 multisig wallet that allows access as long as any combination of 2 of 3 specifically chosen people can still access their private key. Or 3-of-5, or 4-of-6, or 5-of-10, or whatever. That way, even if someone forgets or loses their private key, access to their accounts isn’t lost forever, as long as they have a few family members or friends on the multisig wallet.

But now you have a new security problem to replace the old one: every time you want to do anything with your wallet you need to coordinate with the other members of the group to “sign” your transactions together. This is annoying and time-consuming, especially if you’re not all in the same time zone. So you’ll be tempted to relax the multisig ratio to something less like 4-of-6 and maybe more like 2-of-6.

(Edit: As Twitter user @joshisledbetter pointed out to me after I published this post, it is possible to set up multisigs that don’t require multiple signatures for every transaction.)

But now you’ve created another problem: if you get drunk at the Christmas party and manage to piss off two of your friends at once, you may lose your entire life savings overnight. Or, alternatively, maybe you and all of your multisig friends get drunk together at the Christmas party and lose the slips of paper containing your private keys, at which point the wallet is either forever inaccessible or immediately drained of all of its funds by whoever managed to steal all the private keys.5 Or maybe one of your friends dies and his partner has no idea where he kept his private key, transforming your 3-of-5 de jure multisig into a 3-of-4 de facto one. Or maybe it turns out that, instead of all your friends keeping their private keys secret, they’ve all sent their private keys to their single most trustworthy friend, and then that friend’s house gets burglarized and you lose all your funds. (This is effectively how Axie Infinity lost $600 million.)

And there are even more issues: if you use a single wallet to sign onto everything, this is a far creepier and more invasive form of identity resolution than anything dreamed up by the ad tech industry.6 Why? Because the blockchain is public and every transaction is visible to anyone. Today, privacy-conscious crypto users get around this frightening level of exposure by generating new Ethereum addresses for each separate use case (or even for each transaction), so as to fragment their visible activity and avoid de-anonymization. But in the world of crypto SSO, all of this protection goes right out the window.

In short: thanks, but no thanks. Also, if remembering passwords is such a problem, crypto people should really check out LastPass: it has a free plan! And it works just fine.

Claim #4: Crypto enables streaming payments

Here’s Eliason:

Being able to move very small amounts of money continuously using code is starting to create some interesting use cases. The idea of a biweekly paycheck can quickly become a thing of the past, with people instead getting their salary or hourly payments streamed to them while they’re working.

This introduces quite a few other potential work setups, like being able to charge continuously for consulting work vs. needing to deal with invoicing before and after work is done.

It is true that you can enable streaming payments with crypto. But it is also true that you can do this without crypto. In fact, streaming payments really has nothing to do with crypto at all. Does crypto solve the problem of verifying that you’re actually doing real work for every hour that you’re being streamed your hourly wage? Does something about the blockchain ensure that you get paid promptly rather than thirty days after the fact?

The answer to both of these questions is no. The reason streaming payments isn’t mainstream isn’t because it was technically impossible until crypto came along. It’s because there’s not enough demand for it, or because employers don’t want to pay out contractors before validating the completeness of the work, or because of cashflow issues, or a million other causes. In other words, there are normal human reasons why streaming payments haven’t caught on, which the blockchain doesn’t solve. If the underlying conditions change, perhaps streaming payments will become a thing. But there’s no reason this has to be done using cryptocurrencies.

Claim #5: Crypto makes it easier to establish a reputation

Eliason writes:

If you build a reputation on Twitter, it’s very hard to migrate that reputation to YouTube or Instagram. Most social networks will reduce the spread of media from other social networks because they don’t want you taking your audience elsewhere.

Due to the single-sign-on mentioned earlier, social media in a Web3 world will likely center around following addresses instead of accounts siloed in one service. Since you’ll follow wallets, it won’t matter where they’re posting material. You’ll automatically be following them there…

The downside of a centralized account is that if you develop a bad reputation in one place, it will also be easy to punish you in other places. This could be good in general for weeding out bad actors, but you can imagine how it could be used maliciously too.

Of all the claims in this piece, this is the one that puzzles me the most, because it’s so blatantly incorrect. One of the biggest problems with crypto is that it makes it trivially easy to start over from scratch with a brand-new identity after you’ve nuclear-bombed your previous reputation into smithereens.

And guess who finds this feature particularly valuable? Serial grifters, that’s who. In case you haven’t noticed, the crypto world is disproportionately populated by serial grifters.7

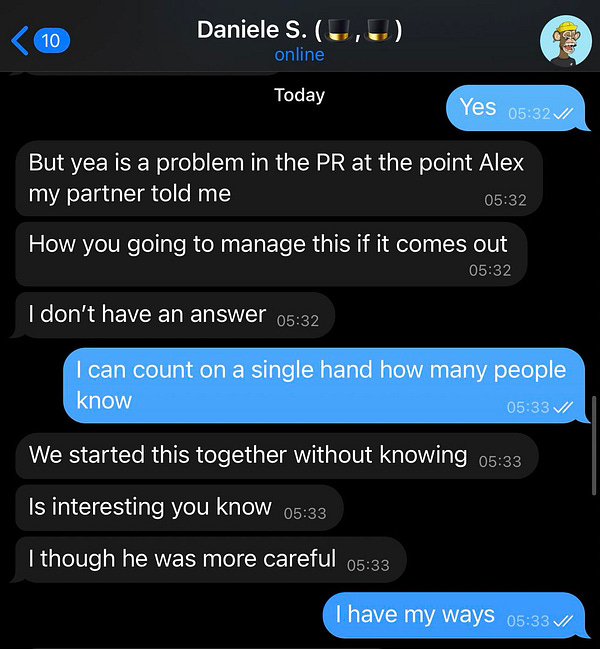

Take “Sifu,” for example, most recently the pseudonymous co-founder of the crypto project Wonderland. In January, crypto investigator @ZachXBT uncovered Sifu’s true identity: he was actually Michael Patryn (previously Omar Dhanani), an ex-convict and repeated scam artist who had also co-founded the Canadian crypto exchange QuadrigaCX, which famously blew up in early 2019 when it turned out Patryn’s co-founder Gerald Cotten had disappeared apparently died only after siphoning about $170 million of his customers’ assets into personal accounts and luxury goods assets.

This is painfully obvious, but it’s worth spelling out anyway: any system that allows you to start over from scratch with a brand-new identity at any time is a godsend for scammers. I mentioned earlier that crypto is disproportionately populated by serial grifters, but it is also disproportionately populated by pseudonymous founders of projects that manage hundreds of millions or even billions of dollars of other people’s money.

The Venn diagram of these two outsized groups is not two separate circles.

In conclusion

These crypto defenses have been circulating for years. And so have, to at least some extent, the critiques. This inexorably leads to the somewhat depressing conclusion that Nothing Matters™️.

But if there’s anytime where perhaps the skeptics sound more credible, hopefully it’s now, following a particularly brutal crypto bear market spurred by extremely old-fashioned financial speculation and the creation of ill-advised unsecured loans.

Crypto is often cheekily described as having speed-run the last millennium of financial history in the space of just over a decade. If so, one silver lining is that the “This Time Is Different” illusions are being shattered much faster in the crypto iteration than they were in traditional finance.

Per Betteridge’s law of headlines, the question answers itself.

This doesn’t always work to perfection. The War on Drugs is a perfect example of the limits of attempting to ban widespread behavior. But again, it is difficult to ban drugs because there is a use case for them: you get high! It’s fun. People like it. There is no equivalent incentive for most normal people to use crypto, especially during a downmarket.

Well, everything except transaction speeds.

Actually, not really.

Per crypto conventions, this will likely be one of your disgruntled coworkers. Keep an eagle eye out for anyone driving a new Lambo.

I would know: ad tech is where I’ve spent my career. One of the idiosyncrasies of online targeting is that it simultaneously enjoys scarily enormous scale (a single company possessing hundreds of millions or even billions of device profiles is not uncommon) and laughably poor accuracy. Go into any third-party data broker’s UI and use Boolean ANDing to join Demographics > Male with Demographics > Female. You’ll likely end up with an audience population on par with the entire Eastern seaboard of the United States.

Although many of them prefer the politer job description of “venture capitalist.”

This is a great article! My only nitpick is that you should be pointing people to Bitwarden, not LastPass. (LP has been collapsing under it's own weight for nearly a decade, and BW's free plan has more features than the former's paid plan.)

Jay - on claim #3: You have overlooked MPC wallets like ZenGo. On-chain, but no private key to have lost or stolen. Uses 3D liveness biometrics to ensure simply recovery (your face) but can't get hacked.

More info here: https://zengo.com/forget-not-your-keys-not-your-crypto-private-keys-are-a-vulnerability/

Cheers!

Ari