Beware of Greeks bearing grifts

A new crypto central bank calls itself Olympus and has a founder named Zeus. But its underlying economics are mostly a tragedy.

Right now I can purchase a three-month U.S. Treasury bill for $99.98, wait three months, and receive $100 in return — a profit of approximately $0.02 for the privilege of helping to finance the operations of the U.S. government.

But what if instead of paying $99.98, I would rather pay $5,000 for the exact same bond, and still receive only the same $100 back three months later?

OlympusDAO solves this.

OlympusDAO calls itself “a decentralized reserve currency protocol,” but you can think of it as a sort of crypto central bank and treasury rolled into one. It issues currency — OHM tokens — just as the U.S. Treasury issues dollars. And just as the U.S. dollar is backed by the full faith and credit of the United States government, OHM is backed by its pseudonymous founder, a suspected teenager who calls himself “Zeus.”1

The Olympus project has gotten a lot of attention lately, not all of it positive. Bloomberg’s Money Stuff columnist Matt Levine describes it as “crypto Ponzi economics,” and his colleague Joe Weisenthal is no more enthusiastic:

It was also cited last week under the subheading “Some in the Crypto Industry have Warned that Olympus DAO may be a Ponzi Scheme” by a witness before the Senate banking committee, which is almost never a sentence you want to hear about your project. Even the first line in a much-discussed and otherwise laudatory CoinDesk piece on Olympus from early December began: “Yes, it’s a Ponzi scheme. But who cares? So are the dollars in your pocket.” (Equating fiat currency to a scam is a common theme in the crypto world.)

And yet Olympus, whose self-reported “market cap”2 exceeds $3 billion, has its fans — and even converts. Nat Eliason, whose “DeFi Fridays” newsletter series is essential reading for anyone trying to understand the basic mechanics of the crypto ecosystem, penned a mea culpa in October titled “I Was Wrong About Olympus:”

It’s hard to admit when you’re wrong. But I was very wrong about Olympus.

When a crypto project has a cult-like following and super high APRs, I usually take that as a sign it’s some kind of scam…

But I was wrong. After months of writing it off, I finally dug into what was going on, and god damn it is a brilliant product. It might be one of the most important DeFi protocols ever built.

And Andrew Thurman, who wrote that CoinDesk piece, concludes:

But my heart is with the frogs. [Olympus’] money isn’t very different from the shoddy, debasing stuff the state forces into our bank accounts (and it’s certainly not dumber).

The problem Olympus solves, according to its announcement post, is “that we still do not have an independently valued digital currency.” It describes the “perfect currency” as one that “holds the same purchasing power today as in 50 years.”

“In the long term,” its web site states, “we believe this system can be used to optimize for stability and consistency so that OHM can function as a global unit-of-account and medium-of-exchange currency.”

This is a lofty, dare-I-say Olympian goal. But what’s actually gotten crypto folks exercised about the promise of OlympusDAO is specifically its innovative approach to maintaining liquidity within the decentralized finance (DeFi) ecosystem. To understand how Olympus is new and different, you first have to dig into how liquidity generally works (or doesn’t) in DeFi today.

Say I’ve just generated a new cryptocurrency, JayCoin, and minted one million tokens of it. Following in the footsteps of previous cryptocurrency projects, I “airdrop”3 — or gift — a bunch of them to friends, family, and influencers in the hopes of incentivizing them to drum up publicity and convince other people to buy some, thereby driving up the price and making themselves a neat little profit.

But how can anyone actually buy, sell, and trade my new JayCoins for other cryptocurrencies? Well, before decentralized exchanges (DEXes) came along, this wouldn’t have been very easy:

Before DEXes, we would have had to email someone at a centralized exchange like Coinbase and ask them to list us. Then there’d probably be months of discussions, paperwork, debates, and we might not even get listed. It would heavily favor companies with huge bank accounts and money to burn. And it would have been slow.

Enter DEXes like Uniswap and SushiSwap. What’s new about these entities is that they’re fully decentralized and noncustodial. Unlike Coinbase, they never hold onto your token balance on your behalf, so you’re always in control of your private keys. You don’t need permission to list your new cryptocurrencies on them. And they also don’t use centralized order books to line up large institutional “market-making” buyers and sellers to settle on a market-clearing price.

So how do DEXes come up with a market-clearing price? They have an automated market maker (AMM), which utilizes a “constant product formula” to generate a currency exchange rate. At its most basic implementation, a constant product formula simply mandates that x*y=k (a constant).

x and y are references to a pair of tokens in a “liquidity pool,” or a currency trading pair. A real-world equivalent might be something like British pounds and U.S. dollars (GBP/USD). In a DEX, however, anyone can create a new liquidity pool from scratch by depositing pairs of tokens.

For example, if I wanted to allow the public to trade JayCoin against ether, I might deposit 1,000 JayCoin and 10 ether into a liquidity pool. 1,000 * 10 = 10,000, which is the “constant product.” Anyone who wants to buy JayCoin must deposit ether into the liquidity pool and withdraw the corresponding amount of JayCoin such that the product of the two tokens — 10,000 — remains constant. (Hence “constant product formula.”)

So if someone wanted to buy 700 JayCoin, thereby leaving 300 JayCoin remaining in the liquidity pool, they would need to deposit about 23.3 ether in exchange, such that the liquidity pool would now consist of 300 JayCoin and 33.3 ether in total, for an unchanged constant product of 10,000. This comes out to an approximate ETH/JayCoin exchange rate of 700 / 23.3 = 30.

One of the key differences from centralized exchanges is that the liquidity, or currency pair, in DEX liquidity pools can be provided by regular crypto users, not just large, institutional market-makers. In order to incentivize those users to lock up, or “stake,” their cryptocurrencies for this purpose and thereby increase liquidity in the crypto ecosystem, the DEX protocol automatically gives these users a cut — usually 0.3% or less — of the value of all trades occurring in that currency pair (proportionate to their share of the total liquidity pool). They do this by issuing liquidity provider (LP) tokens that represent the liquidity provider’s share of profits from trading on the DEX. Additionally, token issuers themselves often incentivize liquidity providers as well, by rewarding them with additional tokens.

This is a genuine innovation. But it has a major vulnerability: the only thing liquidity providers care about is yield, the rate at which their staked tokens earn additional revenue. If and when another opportunity arises to earn higher yield, they’ll redeem their LP tokens for the underlying currency pair and decamp immediately to another exchange or protocol, leaving the original liquidity pool less…liquid.

The net effect of this is that, for any given token such as JayCoin, the amount of liquidity — and thus the ability of users to buy and sell the token easily — is highly fickle and unpredictable. Imagine if tomorrow you tried to exchange your dollars for euros but there were no one around to make you an offer. This is similar to the position many tokens find themselves in today: the market isn’t “liquid” enough for buyers and sellers to easily enter and exit at will.

This problem is exacerbated by the absurd levels of volatility in the crypto ecosystem: since LP tokens are effectively claims on an underlying currency pair, their “profits” are relative to those currencies. That is, if I provide liquidity for an ETH/SHIB currency pair and my LP tokens earn a 10% profit, I may still end up losing real-world money if ETH and SHIB themselves have depreciated against the U.S. dollar in that time.

Olympus believes it’s solved these problems by owning its own liquidity. Before we get into how it works, though…

A brief digression

Olympus claims both that A) “1 OHM is backed by 1 USD” and B) “each OHM is backed by 1 DAI.” In reality, however, Olympus’ “treasury” contains DAI, not U.S. dollars. DAI is a crypto “stablecoin” theoretically backed by U.S. dollars such that 1 DAI = $1, so Olympus is effectively claiming that each OHM token will always be worth a minimum of $1, because every new OHM it mints will have 1 or more DAI corresponding to it in the Olympus treasury.

It is tempting to condense all of the above into a simpler sentence: “1 OHM token is backed by $1.” But that is not strictly true. DAI is itself comprised of a lot of ether and other cryptocurrencies which, in combination, attempt to maintain approximately $1 of backing per DAI token. DAI’s whitepaper calls itself (emphasis mine) “a decentralized, unbiased, collateral-backed cryptocurrency soft-pegged to the US Dollar.”

This complex reality is widely transformed into the less accurate shorthand claim that 1 DAI is equivalent to $1. And that settled conventional wisdom is largely the result of DAI’s parent organization, MakerDAO, repeating it in prominent places like its home page:

And its Twitter feed:

But the reliability of that principle is extremely doubtful in the case of a significant crypto downturn.

It is so doubtful, in fact, that MakerDAO contradicts itself in its own public-facing documents as to DAI’s interchangeability with U.S. dollars:

On the Maker Protocol page: “In extreme events, 1 Dai can be redeemed for \$1 worth of collateral through a process known as Emergency Shutdown.”

On the Emergency Shutdown page: “It is, therefore, possible that Dai holders will receive less or more than 1 USD worth of Collateral for 1 Dai.”

🤷♂️

DAI’s effective equivalence with U.S. dollars is its most important feature — its raison d’être. So the fact that its parent organization isn’t sure if it’s strictly true is…concerning.4 If you visited your bank’s web site and discovered one page claiming you can withdraw your balance at any time and another page saying meh, actually, you might not be able to, this is presumably how fast you’d sprint to your closest local branch to demand all of your cash immediately:

And remember that DAI is the principal currency backing Olympus’ OHM token.

OK, back to our regularly scheduled programming

Right now 1 OHM token is trading at approximately $450. Since Olympus only needs 1 DAI’s worth of assets in its treasury for every new OHM it issues, it has spent most of its existence minting OHM tokens left and right and selling them into the market, currently at close to 450x its underlying “value.” This increases its treasury’s over-collateralization — or “runway,” as Olympus calls it.

OHM is so expensive right now that it’s not just selling at about 450x its minimum collateral backing: it’s currently selling at over 14x the Treasury’s per-token “risk-free value” (that is, its holdings of all dollar-pegged currencies like DAI, FRAX, and others) and almost 6x the per-token market value of all (non-LP OHM) assets in Olympus’ Treasury.

Given all of this, why would anyone in their right mind buy an OHM token for $450? After all, how many successful currencies have you heard of whose primary function is as an investment vehicle? There are two reasons: one short and one a bit longer.

The short reason is that Olympus actually sells OHM tokens directly to users at a slight discount to its market value — the cost of OHM if you were to just buy it directly on a DEX. (Think of this like an employee stock purchase plan, where you can purchase your employer’s shares at a slight discount.) Olympus calls its direct sales “bonding,” as in selling bonds to the market à la the Federal Reserve, because you can buy OHM at a discounted price but must wait five days for it to fully vest.5 So as a short-term strategy, as long as you think OHM’s price is unlikely to decrease much over the next five days6, you can make a profit simply by buying OHM from Olympus and selling it when it vests.

Now, the truly innovative element of this transaction is that the payment Olympus accepts in exchange for minting these bonds is…liquidity pool tokens. In other words, in exchange for you obtaining OHM tokens at a discount to their current market value, Olympus receives a share of its own currency’s liquidity pools, or trading pairs, on decentralized exchanges.

In so doing, it theoretically reduces, or eliminates, the problem faced by so many other tokens: mercenary capital hopping from one investment vehicle to another at the first sign of risk or better opportunities elsewhere. “Owning” its own liquidity ensures that OHM tokens can be traded easily and at large volume in the open market regardless of its price trajectory, just like, say, a large-cap company trading on the New York Stock Exchange.

Indeed, as long as OHM’s price stays above 1 DAI, Olympus can continue minting new OHM tokens, selling them for a profit, and owning more of its own liquidity. If the price dips below 1 DAI, Olympus will buy back OHM tokens at market value indefinitely, again at a profit, and then “burn” them (i.e. remove them from the supply), thereby pushing the price back up to 1 DAI per OHM.

OK, so bonding is the short (and short-term) reason to buy OHM. But it doesn’t really explain why anyone would buy into OHM at current prices and hold onto it. The reason for that is “staking.” That is, once the OHM in your “bond” has vested, you can “stake” it — effectively locking it away, sort of like a certificate of deposit (CD) at a bank.

If you do, Olympus will mint additional OHM — unlike bonding, these new OHM are backed by depleting Olympus’ existing excess treasury reserves, meaning it has a dilutive effect — and subsequently grant them to you over time as a reward for staking. If you don’t stake — that is, if you buy OHM and then just hold onto it — your share of total OHM outstanding will be diluted over time as new OHM are minted and distributed to stakers. So staking OHM effectively just allows you to tread water in relation to the overall supply: your OHM holdings increase along with the total supply of OHM.

Now at this point, you may be thinking to yourself: Waiiiiittttt a minute. So first I have to buy in at an inflated price, and then — in order to maintain (or possibly increase) the value of my holdings over time — I have to lock up my funds in a crypto equivalent of a bank CD.

Yes.

To which your second thought is likely: How is this not just multilevel marketing (MLM) or a Ponzi scheme?7

To which the response is usually some version of: “But look at the annual percentage yield (APY) rewards on this bad boy!”

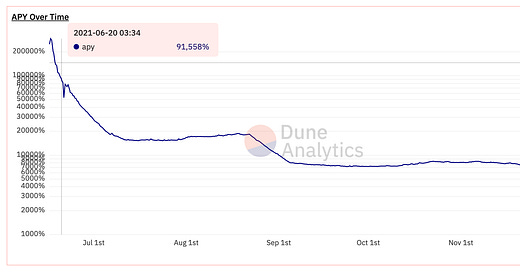

No, the APY on that chart is not a typo, and no, it’s not using the European convention of a comma as a decimal separator. But anyway, don’t worry: as you can see below, following its initial speculative phase, as of mid-December the APY for staking rewards has cooled off to an extremely sensible 5,226%.

So staking a single OHM token now could net you over 50 more by next Christmas.

In short, the appeal of staking takes longer to explain not because its fundamentals are so complicated but because they’re so simple. If you happen to have purchased some OHM tokens from Olympus, you have the following options:

Sell them and pocket the profit (assuming OHM hasn’t depreciated within the five-day vesting period)

Hold them and watch the value get diluted over time as new OHMs are minted but not distributed to you

Stake your OHM and keep pace with “inflation” via ludicrously gargantuan APY rewards

So far, the vast majority of “OHMies” (yes, it’s a thing) have chosen door #3:

In other words, throughout most of Olympus’ existence, about 90% of the OHM in circulation is being staked, or locked up. I have many questions, but for now I’ll just note that a currency for which 90% of its value is untouchable is…generally not a very good medium of exchange.

But even leaving that aside, the basic math is ominous. In order for you to make money — real-world money, as in the kind you use to buy food — via staking OHM, the reward rate for staking needs to be greater than the rate of decline in the value of OHM itself. To take a basic example, if you stake 1,000 OHM for one year and end up with 10,000 at the end of it, but the price of OHM has dropped from $450 to $22.50 in that same timespan, you’ve lost half your money.

And the key point is: some version of this scenario is absolutely going to happen. Olympus itself states that 1 DAI is the “intrinsic value” of OHM, and it’s not committing to backing each OHM with anything more than that.8 To its credit, its announcement post explicitly states:

The best way [to participate] is to buy as close to or below 1 DAI as you can. The distance from 1 is the risk you take on.

And on podcast interviews and in the Olympus Discord chat, Zeus has also made clear that he doesn’t see OHM’s high prices as sustainable.

Olympus’ web site even acknowledges, however obliquely, the absurdity of its token’s current market price. One of the questions on its FAQ page is, helpfully: “What is the point of buying it now when OHM trades at a very high premium?” I will quote the answer in its entirety here:

When you buy and stake OHM, you capture a percentage of the supply (market cap) which will remain close to a constant. This is because your staked OHM balance also increases along with the circulating supply. The implication is that if you buy OHM when the market cap is low, you would be capturing a larger percentage of the market cap.

This is an extremely strange answer. The unstated logic goes something like this:

Yes, you are probably overpaying by an absurd — like, actually genuinely ridiculous — amount of money.

However, others who come after you will continue to do the same thing.

But by then, you’ll have already been staking, and they won’t.

So you’ll own more OHM than they do.

(This photo does not appear on Olympus’ FAQ page.)

The problem, of course, is that there is currently no logical reason why the price should go up indefinitely, or even maintain its current level. It’s supposed to be a currency, after all. Olympus has launched new products — notably Olympus Pro, which gives it a cut of other tokens’ upside — that may hold some revenue potential, but nothing that supports a price 450x its treasury backing.

So, as the price of OHM declines towards its self-described “inherent value,” the APY rewarded to stakers — which, per the above chart, is also declining over time — will begin to look like a very risky proposition. After all, it’s the excess treasury reserves (via the sales of overpriced bonds) that are funding the high APY in the first place.9 (Remember that, while OHM minted by bonding can generate excess treasury reserves, OHM minted by staking rewards can only deplete them.) In such a scenario, stakers will be incentivized to un-stake and sell their positions for literally any other asset, to lock in whatever value they’ve accrued to date before OHM falls further still.

This leaves us with one possible way for Olympus to wriggle its way out of this morass. It could just say, “Actually, the reference point you’re using is all wrong. Stop denominating your value in dollars. Real value is denominated in OHM.”

As it turns out, this is exactly what Olympus is saying. “You can't trust the FED but you can trust the code” is a real sentence that appears on its FAQ page. Olympus sees itself as the heir apparent to sovereign-backed central banks like the Federal Reserve:

This is unfortunate, because Olympus appears to have very little idea how central banking and currency exchange actually work. Let’s head back to its FAQ page:

Is OHM a stable coin?

No, OHM is not a stable coin. Rather, OHM aspires to become an algorithmic reserve currency backed by other decentralized assets. Similar to the idea of the gold standard, OHM provides free floating value its users can always fall back on, simply because of the fractional treasury reserves OHM draws its intrinsic value from.

Zooming in on this part:

Similar to the idea of the gold standard, OHM provides free floating value…

Free-floating value is quite literally the opposite of the idea of the gold standard. The Bretton Woods system, agreed to in 1944, codified the establishment of fixed exchange rates between the U.S. and other countries, as well as convertibility between the U.S. dollar and gold at $35/ounce.

This is not Zeus’ first run-in with the historical record. In a podcast interview in June, he said:

No one really complains about the dollar pre-1970, back when it was backed by gold. Things actually worked pretty well — probably the largest economic expansion in human history. But then you had this departure from the gold standard, you had just now full fiat. This is backed by nothing, and it went pretty poorly after that.

This is an odd thing to say. Even leaving aside the overly simplistic economic history, how can all of the following things be true at once:

A) The perfect currency is one that retains constant purchasing power over a 50-year period

B) No one complained about the pre-1970 dollar

C) In the five-year period from 1965 to 1970 alone, cumulative inflation in the U.S. totaled 23.2%

Or stated in simpler terms: if “no one really [complained] about the dollar pre-1970,” why did Richard Nixon get rid of it in 1971?

The answer, while complicated, was partly inflation — that crypto-world bugbear that supposedly can only happen in a world of free-floating currency. As Zachary Carter explains in his masterful book The Price of Peace, “The United States had been leaking gold for years thanks to inflationary pressures and the new phenomenon of an American trade deficit.” As you can see clearly from this chart, elevated inflation is not solely a post-Bretton Woods phenomenon:

In fact, the current annual inflation rate in the U.S. — which has prompted howls of criticism from the libertarian-leaning crypto community — is roughly in line with where it was in the summer of 1970, before the U.S. abandoned the gold-backed Bretton Woods system.

This is not the only aspect of banking Zeus misunderstands. In the same June podcast interview, he was asked what a crypto reserve currency is supposed to accomplish:

In my mind, it really comes down to liquidity…The real goal in my mind is to have something where, when there’s excess demand, there’s people to sell to it. When there’s excess supply, there’s people to buy from it. Whenever there’s a trade being made, there’s someone on the other side of it.

This is actually what central banks primarily do, is they provide liquidity.

This is not true. The primary purpose of the central bank, at least in the U.S., is the famed “dual mandate” of maximum employment and stable prices (i.e. low inflation), which the Fed achieves by setting the short-term interest rate via open market operations.

Yes, the Fed also provides liquidity to its member banks, but in normal (non-emergency) times this is an almost negligible aspect of its function, and is certainly not what it “primarily” does or is intended to do. A Congressional Research Service report from February underscores this point:

The Federal Reserve (Fed), as the nation’s central bank, was created as a “lender of last resort” to the banking system when private liquidity becomes unavailable. This role is minimal in normal conditions but has been important in periods of financial instability, such as the 2007-2009 financial crisis.

As then-Vice Chairman of the Federal Reserve Stanley Fischer cautiously celebrated in 2016: “While we have likely reduced the probability that lender of last resort loans will be needed in the future, we have not reduced that probability to zero.”

Needless to say, this is not the rhetoric of an institution whose primary purpose is providing liquidity. When a typical consumer buys bonds for their investment portfolio, they generally do it via a brokerage like Fidelity or Schwab precisely because there’s so much liquidity in the bond market already. “Lender of last resort” is the last resort for a reason. (This is also, as it happens, why not “owning its own liquidity” is not a problem for the U.S. government: unlike OHM, U.S. dollars are widely valued, so the government doesn’t need to become the dominant participant in retail foreign exchange markets simply to prevent a complete loss of confidence in the dollar.)

Given these inaccuracies about central banking as it exists today, it’s worth asking what Olympus thinks central banking should do.

There’s a distinct dog-that-caught-the-bus quality to the Olympus project: its implicit first principle is that sovereign central banks are bad, but given the chance to define itself in opposition, it falls into near-monastic silence. Price stability is bandied about, but stability relative to what? It’s not that Olympus has a bad answer to this question. It has no answer to this question.

I mean that literally. In a Discord thread earlier this year, Zeus was asked what would be a good metric to measure OHM’s price stability against. It’s worth reposting the entire conversation:

This is not a sentence I ever thought I’d write, but: “cryptofreebies” is spot-on here. “Price today being similar to price yesterday” needs to be denominated in something to have meaning. It also needs to be measured against a relatively stable basket of goods in order to be comparable over time. If only we had a way to do that.

In addition to the gaping vacuum of information on how the OHM currency will achieve price stability, Olympus also appears to have no strategy on how to become a currency anyone actually uses in the long run. The steps seem to be:

Rake in cash from overeager buyers.

….?

Become the world’s reserve currency.

This is a Benjamin Button-esque vision of currency creation. Generally, the best way to bootstrap currency adoption is to force citizens to pay their taxes in it, backed by a credible threat of force. Olympus intends instead to reverse-engineer this process: first, it generates billions of dollars of assets and then, through some automagical but undefined process, OHM becomes used everywhere.

And the problems don’t end there. If the U.S. dollar is such a problematic foundation for the global economic ecosystem, how is OHM planning on independently maintaining price stability while simultaneously guaranteeing a 1 DAI minimum backing? This would be like the British government allowing the pound sterling to float in currency markets while also promising it will always be worth at least $1.

This cognitive dissonance extends to Olympus’ adherents. Near the end of Nat Eliason’s “I Was Wrong About Olympus” essay, he enthuses about the backstop provided by stablecoin assets in Olympus’ treasury:

So if the community lost 100% of their faith in OHM and it had no speculative value, there would still be ~$30 per OHM token in existence. That’s quite a bit lower than the current price of $866, but considering most coins don’t have any backing like this, that’s pretty nice.

But this only serves to underscore the project’s absurdity: in what universe is it reassuring that a token you could once buy for $866 will always be worth at least $30? If the answer to that question is “one in which Olympus is a global reserve currency,” then OlympusDAO is perhaps one utopia we can all live without.

Appendix: Reading List

Decentralized Exchanges: Why Crypto’s First Killer Apps are So Powerful

150% APR? How Are DeFi Yields So High?

OlympusDAO’s decentral bank — what might stop DeFi’s “liquidity black hole?”

A 7,000% APY Crypto Token | $OHM Investment Memo

Talking Crypto #72 - Zeus from Olympus DAO

Up OHMly featuring Zeus & JaLa

No One Understands Olympus DAO

Additionally, I would like to thank my buddy Ariel Stulberg for being a constant sounding board and debating partner on all things finance and crypto.

CORRECTION: This post originally stated that OHM is “currently selling at over 25x the Treasury’s per-token ‘risk-free value’…and over 60x the per-token market value of all (non-LP OHM) assets in Olympus’ Treasury.” This has been corrected to “over 14x” and “almost 6x.”

On why he chose the moniker: “Like, I think the Greek mythology has this, like, really deep-seated, like, place in culture. So, you know, if you kind of think of, like, what are the most familiar, like, ancient cultures to people, you know, Greek is probably on the top of that list.”

Not a term you typically see associated with currencies.

And just like the recipients of strangers’ unsolicited AirDropped dick pics on the subway, those on the receiving end of crypto airdrops are often disinclined to accept them as well.

And this is before we even get into the conditions that prompt the “emergency shutdown” procedure, one of which is “long-term market irrationality” — a scenario that has somehow not yet been triggered by anything that’s transpired in the crypto world over the past, say, five years or so.

A five-day Olympus bond is the crypto equivalent of a thirty-year U.S. Treasury, in the sense that the probability of default of each bond’s underlying currency within their respective timespans is roughly similar.

To paraphrase Matt Levine, this is definitely not investment advice. As seen below:

Look, I never said this wasn’t a Ponzi scheme — although, if it is, it’s a rather delightful twist on one, given that all the math is right out in the open. It’s sort of like robbing a bank without a ski mask: yes, people will lose their money and be very sad, but you didn’t exactly trick anyone.

The truth is actually worse: Olympus doesn’t really back OHMs at all. Per the CoinDesk piece from earlier this month: “The treasury, the most heavily relied-upon fallback believers invoke, means next to nothing. At least at the moment, the widely touted ‘backing’ the treasury provides is effectively nonexistent…OHM cannot be directly redeemed for a proportional share of Olympus’ treasury.”

So Olympus’ backing is akin to me giving you 100 pieces of paper and saying, “Don’t worry, I have $1 in the bank for each of those pieces.” I may be telling you the truth, but that doesn’t mean I’m going to give you any of my dollars in exchange for the papers.

In one important sense, this is all a bit academic: in a world where 90%+ of OHM are staked, the reward APY is basically meaningless anyway, because almost every OHM holder is both A) gaining new OHM and B) being diluted at the same rate. (As Olympus’ docs state: “When you buy and stake OHM, you capture a percentage of the supply (market cap) which will remain close to a constant.”) At that point it’s more or less a stock split.

I discovered this project a while ago. The fact they advertise a four figure APY and not obviously mention that it's a rebasing token was a big red flag for me. They should be using inflation-adjusted-return as the advertised metric. The bonds-as-a-service (BaaS) offering does spark my interest though. Also seeing interesting liquidity innovations coming out of Tokemak & Ondo.