(Don't) Meet the Press

Let's dispel with this fiction that Chuck Todd doesn't know what he's doing. He knows exactly what he's doing.

It's weird, in retrospect, to look at newspaper headlines from just before the Capitol Hill riot on January 6th.

Two days beforehand, The New York Times published a piece about the upcoming electoral vote certification titled “Pence’s Choice: Side With the Constitution or His Boss.” The article itself was fairly by-the-book, but it’s hard to glide past a headline casting the vice president’s constitutionally mandated role as an equally valid alternative to…breaking the law. (Area Burglar’s Choice: Shoot the Cashier or Just Pay for the Wheaties Like Everyone Else.)

And so the question being asked in a pair of pieces this month, by New York Times Magazine contributor Jason Zengerle and The New Republic’s Meredith Shiner, feels especially germane in the post-riot aftermath: will anything in journalism change in response to the ongoing democratic threat posed by the Republican Party?

In “The Capitol Riot Killed ‘Both Sides’ Journalism,” Shiner doesn’t exactly say it will change, but that it should:

The work of undoing decades of “training” in divorcing humanity from political coverage will not happen overnight. I keep thinking about the House impeachment managers who repeatedly have asked, “if this is not an impeachable offense, what is?” And I have asked myself, if this is not the event that frees reporters from the chains of “both-sidesism,” when one side, the Republicans, contributed to an attack in which reporters almost died, what will?

Zengerle doesn’t so much as dare to dream. In “How the Trump Era Broke the Sunday-Morning News Show,” he concerns himself less with diagnosing the underlying cause of journalism’s ills and more with identifying the repeatable symptoms:

Earlier that same month, [NBC’s Meet the Press host Chuck] Todd again hosted [Republican senator from Wisconsin] Ron Johnson, who again used the opportunity to spew nonsense, boasting about a recent hearing he had held to look into allegations of voter fraud. “The fact of the matter is that we have an unsustainable state of affairs in this country where we have tens of millions of people that do not view this election result as legitimate,” Johnson said at one point.

“Then why don’t you hold hearings about the 9/11 truthers?” Todd asked. “How about the moon landing? Are you going to hold hearings on that?”

It was a good line, and Todd seemed pleased with himself. It did not occur to Todd, however, that the same question could be asked of him. If “Meet the Press” is going to have guests like Johnson, why doesn’t it host 9/11 truthers and moon-landing conspiracists as well?

This point has been made by plenty of others, including frequent media critic Matt Negrin, whose Twitter timeline often resembles a Munchian scream into the void:

Slightly less angrily, perhaps, The Bulwark’s Jonathan V. Last — reacting to a mealy-mouthed impeachment statement by Marco Rubio1 — levied a more specific version of this argument in a newsletter titled “Ask Every Republican These Two Questions:”

A proposal for reporters covering Republican candidates and officeholders over the next four years:

Every interview should begin with two questions.

Sir/Ma’am, I need one-word answers from you:

Who won the 2020 U.S. presidential election?

Was this the legitimate result of a free and fair election?

This shouldn’t take long. The questions can be asked in less than 5 seconds. The answers are one word each: “Biden” and “yes.”

Any Republican candidate or officeholder who refuses to answer, or who tries to elide the question by saying something like, “Joe Biden is the president,” should be asked again. And again. And again.

In fact, just such a litmus test has recently been tried. Zengerle quotes from an ABC News interview of Senator Rand Paul by anchor George Stephanopoulos in late January, in which Stephanopoulos did almost precisely what Last proposed:

As you can see above, Paul lied, whined, and interrupted his way through a badgering response that culminated in an Orwellian lecture on media ethics:

Where you make a mistake is that people coming from the liberal side like you, you immediately say everything’s a lie instead of saying there are two sides to everything. Historically what would happen is if I said that I thought that there was fraud, you would interview someone else who said there wasn’t. But now you insert yourself in the middle and say that the absolute fact is that everything that I’m saying is a lie…

There are two sides to every story. Interview somebody on the other side, but don’t insert yourself into the story to say we’re all liars…

This li(n)e is astonishing for its chutzpah — there are certainly not two sides to the story of widespread election fraud, which didn’t happen — but it is also an eerily accurate summation of what Republicans have long viewed as their birthright in interactions with newspapers and national TV news channels: the ample time and space to propagate conspiracies, disinformation, and hoaxes directly to the American public, often with minimal to no pushback from their interlocutors.

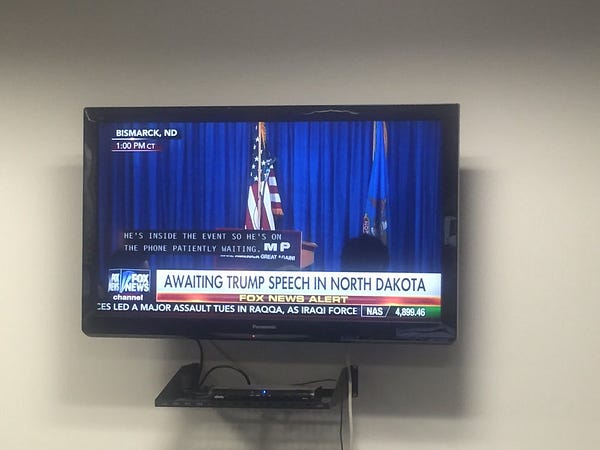

In retrospect, the infamous live shots of empty podiums prior to Trump campaign speeches in 2016 — perhaps the apotheosis of this journalistic laissez-faire approach to political disinformation — were a foreboding omen for the integrity of the American press corps:

But they are hardly the only egregious examples. Zengerle notes that Sunday-morning shows like Chuck Todd’s Meet the Press “became platforms for disinformation.” As Washington Post media columnist Margaret Sullivan observes:

Journalists long ago made a virtue of getting input from both sides of an issue. It’s generally a healthy practice, but it also became a crutch. And when one side consistently engages in bad-faith falsehoods, it’s downright destructive to give them equal time.

Joe Lockhart, President Bill Clinton’s former press secretary, offers an extreme example: “If I went on the air and said the Holocaust didn’t happen, the interview would end right there.”

Similarly, the election-fraud lie — which was the foundation for the Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol — shouldn’t be given a huge megaphone either.

I have written at (extreme) length about the ways in which the media wrongly treats Democrats and Republicans as flip sides of the same coin. (“There are two sides to every story!”) Inviting prolific Republican liars onto TV shows to spout absurdities is just one specific manifestation of this impulse, but one that deserves a spotlight of its own — as it openly conflicts with journalism’s ostensible mission to educate the public. Exactly what educational purpose is served by another Ron Johnson or Rand Paul interview, even one in which the host aggressively rebuts their lies about the 2020 election? Or how about transforming a tick-tock account of Trump’s final days in office into a wholesale reputational makeover of former attorney general and known liar Bill Barr? Or the countless times Kellyanne “Alternative Facts” Conway was invited onto TV news shows?

These questions all share the same answer: none. Which leaves hosts like Chuck Todd in a peculiar dilemma. Their paychecks depend on the combination of an encyclopedic knowledge of American politics and an innate sixth sense for how to please the ratings gods, but the TV moments that consistently generate virality and bombast — and, therefore, job security — are precisely those where those two traits are in open conflict: known peddlers of disinformation repeating their well-worn lies to TV hosts who are well-acquainted with the spin but must react as if they aren’t.

And thus there’s something almost sinister about these TV newsmen’s thin veneer of shocked innocence. Chuck Todd has created a mini-cottage industry unto himself of being surprised by the mendacity of his own TV show’s guests. In the span of a single 2019 Rolling Stone profile, he performed ritual self-immolation in a way that suggested either gross professional incompetence or studied insincerity, neither of which are a particularly good look for one of the most influential journalists in the country.

On former press secretary Sean Spicer lying about Trump’s inauguration crowd size: “I guess I really believed they wouldn’t do this. Just so absurdly naive in hindsight.”

On Ted Cruz spreading disinformation on Todd’s own show about Ukrainian election meddling: “I did not expect [Cruz] to do this…I was stunned because he’s a Russia hawk.”

And then, in whatever is the opposite of introspection: “I don’t get why so many people are comfortable uttering stuff that they may know will look ridiculous in three or four years.” (Perhaps because they keep being invited onto prominent national TV shows to discuss them?)

At one point he asks, rhetorically: “My fear is the next news consumers: How will they know truth from fiction? How will they have the tools to discern from this?”

It’s a good question, Chuck. But it’s not one to which anyone will find an answer on Meet the Press.

Rubio is, of course, the inspiration for this newsletter’s sub-headline.