Axios of evil

On the American press and the disembodied politics of 'mischief making.'

1 big thing

On Thursday Axios published a piece titled “The Mischief Makers,” about a list of “Republican and Democratic lawmakers…emerging as troublemakers within their parties and political thorns for their leadership.”

On the Republican side were Congresspeople including Marjorie Taylor Greene, Matt Gaetz, and Louie Gohmert. To call these members “mischief makers” is, at best, a wildly generous understatement.

Congressional freshwoman Greene is a prominent QAnon conspiracy theorist. She endorsed political violence just before last year’s election. Her social media likes and posts have implied support for executing Nancy Pelosi, Hillary Clinton, Barack Obama, and “deep state” FBI agents. She has expressed agreement with posts alleging that the Parkland and Sandy Hook school shootings were staged. Of September 11th, she claimed that “it’s odd there’s never any evidence shown for a plane in the Pentagon.” She blamed California’s gargantuan 2018 Camp Fire on “a laser beam from space” (financed by — who else? — the Rothschilds). She called Jewish Democrat George Soros, a frequent and high-profile victim of anti-Semitic smears, a Nazi.

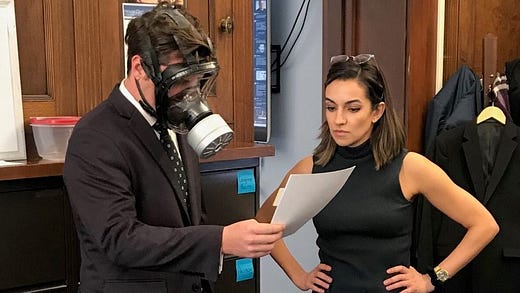

I’m doing Matt Gaetz a favor by covering Greene first: he only looks less insane by comparison. Gaetz famously wore a gas mask on the House floor last year to mock coronavirus concerns (before contracting COVID-19 himself). In a made-for-TV stunt during the first Trump impeachment trial, he led a few dozen Republicans in storming the secure room where witness depositions were taking place to protest a nonexistent lack of access. (“It was [the] closest thing I've seen around here to mass civil unrest as a member of Congress,” said one congressperson last seen being inducted into the Spoke Too Soon Hall of Fame.) As a Florida state representative, he claimed open carrying of guns was a right “granted not by government but by God.” He used crowd-sourced suggestions from the now-banned r/The_Donald subreddit to introduce a resolution that indicated, among other things, that former FBI director James Comey had been leaking information to New York Times journalist Michael Schmidt when the reporter was only ten years old. Like Greene, Gaetz also jumped headfirst into George Soros conspiracies.

And then there’s Louie Gohmert. Oh, Louie.

Louie Gohmert is a thoroughly, devastatingly unintelligent man. Set against Gohmert’s fever dreams, space lasers and ten-year-old investigative journalists are the veritable equivalent of Einstein’s theory of relativity. (A theory funded, no doubt, via Rothschild profits from Jewish space lasers.) He based his support for a trans-Alaskan oil pipeline on caribou mating: “So when they want to go on a date, they invite each other to head over to the pipeline.” He wandered into a spat with Pope Francis over his support for combating climate change: “Since when does science not allow opposing viewpoints?” This past spring he claimed that German hospitals had developed a “disinfectant powder” that kills COVID-19: “Health care workers go through a misting tent going into the hospital and it kills the coronavirus completely dead.” Perhaps he should have nabbed some “mist” for himself: Gohmert (who had made a point of not wearing a mask) contracted the coronavirus in July, and quite sensibly concluded it was likely caused by wearing his mask. Oh, and he also trafficked in anti-Semitic George Soros conspiracies.

The other side of Axios’ “Mischief Makers'“ scale includes Democratic progressives Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Ilhan Omar, Rashida Tlaib, Ayanna Pressley, Jamaal Bowman, and Cori Bush, whose troublemaking Axios summarizes as “[breaking] with leadership on crucial votes,” “voting against a waiver for retired Gen. Lloyd Austin to serve as Defense secretary,” and “[pushing] back against…Obama, after he dismissed ‘defund-the-police’ as a slogan.”

Go deeper

If the difference between these two groups of people feels slightly like the gulf between the subjects of a Jane Goodall documentary versus, oh I dunno, C-SPAN, you’re probably not sophisticated enough to be an Axios reader.

Welcome to the world of D.C. political journalism, a place where civic and moral judgments are verboten, false equivalence is the coin of the realm, and the political horse race reigns supreme. This is a world pioneered in large part by Politico, evangelized by Axios and Punchbowl, and — perhaps most disconcertingly — perpetuated, to varying degrees, by much of the American political journalism establishment.

For an industry ostensibly designed to foster public accountability, there is virtually no universe as cloistered and cosseted as national political journalism in the United States. (Just look at the many rarified perches from which prominent Iraq War supporters continue to earnestly peddle their journalistic wares in 2021.) Politics is, ultimately, about the tussle between warring ideologies and how those battles result in policies — on healthcare, wages and the workplace, travel, food safety, the environment, and so much else — that profoundly affect the lives of hundreds of millions of people. You would think political journalism would reflect that gravitas in its coverage.

But in the hands of nihilistic news outlets like Axios, politics as entertainment is often forcibly disembodied from broader society and wholly detached from the real-world consequences of politicians’ actions. Casting moral aspersions, no matter how obvious or justifiable, on a politician or political party for their own actions is Simply Not Done™️ (said in the best Victorian-era headmistress voice). Neither is aggressively covering the starkly asymmetric extremism coarsing through the American right’s bloodstream. Doing so would jeopardize source access, the social currency that underpins the business model. The point is to document political power, not to question it.

This endless landscape of lowest common denominators was forged by Politico and its famed Playbook newsletter. (As you’ll soon see, sports metaphors are no strangers to political journalism.) It’s no coincidence that the newsletter’s star author, Mike Allen, was a founding member of Politico before leaving to co-found Axios, where he now runs its Axios AM and Axios PM newsletters.

I’ll put this as generously as possible: Mike Allen’s sense of journalistic ethics is remarkably…loose. As The Washington Post’s Erik Wemple has amply documented, Allen’s Playbook was rife with native ads interspersed near-indistinguishably with organic ‘reporting’ that covered the sponsors in the same glowing terms as the ads did. (Here’s a Politico colleague, damning Allen with faint praise: “Sources give stuff to Mike Allen because…they know he’ll play it totally straight, not letting any dissenting voices muddy up whatever PR the source is trying to get out.”)

Allen was once forced to publicly apologize for promising Chelsea Clinton’s staff the right to select in advance which interview questions he’d ask her during a public Politico event: “No one besides me would ask her a question, and you and I would agree on them precisely in advance.”

In a 2010 New York Times Magazine profile of Allen (then at Politico), Mark Salter, John McCain’s one-time aide, said of Allen’s employer: “They have taken every worst trend in reporting, every single one of them, and put them on rocket fuel…It’s the shortening of the news cycle. It’s the trivialization of news. It’s the gossipy nature of news. It’s the self-promotion.”

Allen’s departure from Politico didn’t alter the newsroom’s gossip-driven mandate. Just weeks ago, the Playbook newsletter began hosting guest writers (starting with the recently fired Times editorial page editor James Bennet).

After featuring progressive TV host Chris Hayes on January 13th, Playbook handed over the reins to far-right bigot and racist provocateur Ben Shapiro, who promptly exploited Politico’s borrowed megaphone to whine at length about the unfairness of lumping in the GOP with the Capitol rioters. When over 200 Politico staff joined a call convened by editor-in-chief Matt Kaminski to address newsroom furor over the decision, Kaminski declared: “Mischief making has always been a part of Politico’s secret sauce.”

Different publication, but the same parlor game: QAnon adherence, anti-Semitism, COVID conspiracy theories, violent rhetoric, bigotry, and racism.

You know, mischief making.

The big picture

I’m picking on Mike Allen, Politico, and Axios because (like much of their journalism) it’s remarkably easy. But they are hardly the only culprits here.

Another member of the same spiralling journo-cinematic universe is CNN’s Chris Cillizza. (Back in 2005 he was hired by The Washington Post’s John Harris, who would later co-found Politico.) Cillizza is the archetype of the reporter at the nexus of journalistic nihilism, factual relativism, and professional malpractice that characterizes much of national political reporting today. The man once described his reportorial philosophy thusly:

My job is to assess not the rightness of each argument but to deal in the real world of campaign politics in which perception often (if not always) trumps reality. I deal in the world as voters believe it is, not as I (or anyone else) thinks it should be.

Elsewhere, as if to prove his point, he was asked what sounds like a fairly straightforward question:

Q: Chris, does the Constitution exist?

A: Maybe you misunderstand what I do. I’m not here to debate whether or not the Constitution is a factual object. I’m here to discuss how politicians are received when they debate whether it exists as a document or not.

Or take Punchbowl as another example. Like a disease spreading slowly outward, several years after Politico alumni launched Axios (“Rule number one is we don’t ever want to dumb it down”), still other Politico employees sprouted Punchbowl, a newsroom to focus on Congressional coverage, earlier this month.

The name, a reference to the Secret Service codeword for the U.S. Capitol building, is a knowing wink to political insiders, the type of people who derive social status from lobbing politically esoteric marginalia over hors d’oeuvres on a first date.

Just after the new year, Times media columnist (and Politico alumnus) Ben Smith interviewed Punchbowl founders John Bresnahan, Jake Sherman, and Anna Palmer. Acknowledging that “the notion of covering politics as an amoral sport has become repellent to Americans,” Smith rhetorically wondered, “How do you cover a Republican Party that votes to overturn an election?” Smith then proceeded to answer his own question: Punchbowl is “less concerned with those big questions.”

In the piece, which posted three days before the actual “Punchbowl” was overrun by fascists and conspiracy theorists hunting down members of Congress, Smith asked Bresnahan whether journalists should cover the GOP as a “toxic anti-democratic sect” for their planned upcoming vote to overturn the election results:

“I don’t think it’s incumbent on me to say, you know, to necessarily brand a person a liar, say that they’re disloyal to the country or anything like that,” Mr. Bresnahan said. “But what is important for what we do is to say, Why is this person is doing that?”

Similarly, last summer in Playbook, Punchbowl founder Jake Sherman dismissed the Trump administration’s violation of the anti-corruption law prohibiting elected officials from using their government resources for campaign purposes: “But do you think a single person outside the Beltway gives a hoot about the president politicking from the White House or using the federal government to his political advantage?”

And two weeks ago, in a CJR interview (in which he previewed a potential Punchbowl TV show modelled on ESPN’s Pardon the Interruption), Sherman endowed his new organization with his own anthropological view of politics:

[W]e want to chart power. Our goal is to chart power and to focus on the one hundred people that matter…We are writing about power, the exercise of power, and people abusing power.

He forgot one small detail: Punchbowl is also sponsored by power.

You would be hard-pressed to pick any two American corporations less appropriate to sponsor a newsroom (space) laser-focused on Congress than Facebook and Amazon. Just under four months ago, the House Judiciary Committee’s Antitrust Subcommittee released a blistering 450-page report that directly accuses Facebook of “[maintaining] its monopoly through a series of anticompetitive business practices” and states that Amazon “has engaged in extensive anticompetitive conduct in its treatment of third-party sellers.” Joe Biden’s transition team recommended an aggressive antitrust posture towards big tech companies as well. In short, many signs point to a battle royale between Congress and Big Tech in the months to come.

So will the sponsorship of major newsroom projects by the very targets of these investigations have any impact on Punchbowl’s ability to write about “the exercise of power?”

The revolution will not be televised

If you think digital political coverage is vapid and detached from the consequences of policies, try turning on your TV. During Donald Trump’s 2016 presidential campaign, now-disgraced CBS head honcho Les Moonves famously declared: “It may not be good for America, but it's damn good for CBS.” The next year, CNN Worldwide president Jeff Zucker boasted: “The idea that politics is sport is undeniable, and we understood that and approached it that way.”

Indeed, the TV interview ‘takedown’ became such a ubiquitous staple of the Trump era precisely because it masqueraded as an emblem of journalists’ effortless toughness rather than an indictment of their undiscriminating booking practices. New York Times television critic James Poniewozik drily described the underlying environment: “Politics has become mostly affective anyway. It’s about the delivery of emotions…not getting some actual deliverable like a bill passed or whatever.” (Or whatever!) And he summed up the Trump-era television dynamic thusly:

I do not believe that one could have someone go directly from hosting a TV program, like Trump did, to then becoming president of the United States until you had a media environment where politics was basically a form of entertainment combat that was carried out through the media.

The only TV conflicts more prevalent than the ones designed for the cameras are the ethical ones taking place offscreen. MSNBC alone employs two prominent personalities who famously lied in ways that directly impugned their personal integrity and belie their positions as trustworthy arbiters of news coverage.

In 2015, Brian Williams was temporarily suspended from NBC News for making up a story about being on a U.S. military helicopter that was fired upon while he was reporting from Iraq. Ian Millhiser, who jokingly called Williams the “first person in human history to suffer professional consequences for lying about the Iraq War,” became yet another inductee into the Spoke Too Soon Hall of Fame: Williams made his return (to MSNBC this time) just seven months later and now hosts his own show, The 11th Hour.

In 2018, a series of old blog posts by Joy Reid, who then hosted the MSNBC show AM Joy, surfaced in which she made homophobic comments and attempted to out prominent politicians (like the then-governor of Florida) that she suspected of homosexuality.

In her ‘apology,’ Reid stated that “I genuinely do not believe I wrote those hateful things because they are completely alien to me” and even claimed she had hired cybersecurity experts to investigate the possibility that her blog had been hacked into. (In a shocking turn of events, no one found any proof.)

Last year Reid was promoted to a primetime slot and given a new show.

Be smart

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the endless false equivalence, moral timidity, and ethical ambivalence documented above also result in bad and boring journalism, even on these reporters’ own narrowly defined terms.

In the interview with Ben Smith, Punchbowl’s Jake Sherman teased his project’s secret sauce:

“There is a segment of the world that thinks Mitch McConnell is the devil and just wants to read nasty stuff about Mitch McConnell all day long,” Mr. Sherman said in an interview. “But there is a massive segment of the world who wants to understand what Mitch McConnell does and why he’s doing it.”

In the CJR interview several weeks later, Sherman reached for the same example to elucidate Punchbowl’s raison d’être: “We’re explaining what Mitch McConnell is doing before he does it and why he’s going to do it.”

We finally got a sneak peek of Sherman’s cutting-edge McConnell analysis in a new Deadline interview posted Friday:

Mitch McConnell cares about one thing, and it is winning…His view of the world is very kind of black and white, which is, he’s going to use his power to its maximum effort and its maximum velocity, and the only way to stop him is to have the votes to stop him…People overanalyze him, when it is really that black and white…

Nancy Pelosi and Mitch McConnell’s politics could not be more different, but they execute power in a very similar way, where they have a goal in mind and then singlehandedly work toward it.

I’ll leave it to others to determine whether this GPT-3-level punditry, in which McConnell’s view of power is indistinguishable from that of your local postman or Thomas the Tank Engine, is worth the $300 annual membership fee.

But Sherman doesn’t stop there. He also prognosticated about the outcome of Trump’s upcoming (second) impeachment trial:

Republicans are not going to vote to convict Donald Trump in big numbers. They’re going to vote to acquit him, and there’s nothing that’s going to change that, that we can see right now. I wonder when people are going to kind of realize that…When I’m talking to people on Capitol Hill, they don’t understand how people are getting the story so wrong.”

But, but…are people getting the story so wrong? On January 25, The New York Times reported: “Few Republicans appeared ready to repudiate a leader who maintains broad sway over their party by joining Democrats in convicting him.” The next day, The Wall Street Journal wrote much the same — “Ahead of the vote Tuesday, a Wall Street Journal survey found that at least 32 senators have said they are opposed to a trial or leaning against convicting Mr. Trump.” — and The Washington Post ran a story headlined: “Nearly all GOP senators vote against impeachment trial for Trump, signaling likely acquittal.”

Or let’s switch over to Axios’ “Mischief Makers” piece. It creates a grotesque false equivalency between the GOP’s right wing and the Democrats’ left wing, sure, but is its political handicapping accurate at least? Well, if Marjorie Taylor Greene is truly, as they report, such a “political [thorn] for their leadership,” House GOP leader Kevin McCarthy certainly has a strange way of showing it: he just appointed her to the education committee this past week.

How about Chris Cillizza? Well, if penning articles with titles like “A second-by-second analysis of the Trump-Macron handshake” and “Donald Trump just held the weirdest Cabinet meeting ever” counts as high-quality journalism, you may as well cancel your New Yorker subscription right now. Slate’s Will Oremus said it best: “It stands to reason that someone, somewhere, thinks Chris Cillizza is good at political commentary.”

Why it matters

As the #MeToo movement emerged toward the end of 2017, we collectively began to learn that many of America’s top male journalists, whose negative, persnickety coverage of Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign the year prior had helped cement her public image as cold, shifty, and corrupt, were, in fact, serial sexual harassers or abusers. Roger Ailes, Bill O’Reilly, Matt Lauer, Mark Halperin, Leon Wieseltier, and others — abusers and harassers all, but also guardians of our national conventional wisdom.

Of these “lecherous men,” Rebecca Traister lamented: “We can’t go back in time and have the story of Hillary Clinton written by people who have not been accused of pressing their erections into the shoulders of young women who worked for them.”

The press failures covered in this newsletter are (thankfully) less extreme: they comprise professional dereliction rather than criminal behavior. They are different in another way, too: today, contra 2017, as we survey the (literal) wreckage of the Capitol grounds, we have a distinct advantage in judging our national press corps. We don’t have to wait for a tsunami of new revelations to know we have a problem.

This problem isn’t limited to Politico, Axios, and Punchbowl. And it’s not sufficient to throw in CNN and MSNBC. Due to consolidation and the brutal economics of newsgathering, the ‘Politico effect’ has widened to encompass much of our national journalism scene.

At The New York Times alone, in addition to Ben Smith, the list of Politico alumni covering politics includes Maggie Haberman, Jonathan Martin, Ken Vogel, and Glenn Thrush. (I’ve probably missed many others.) Much of their work (like much of Politico’s) is thorough and laudable. But a nihilistic through-line remains.

In a 2017 TimesTalks panel featuring executive editor Dean Baquet, Haberman, Jim Rutenberg, and chief White House reporter Peter Baker (whose wife is a Politico journalist), journalistic relativism was elevated to canon.

Baquet, answering an audience question about why it took so long for the Times to call Trump’s lies lies, said of such words: “They’re facile. They’re meaningless…I actually think using the word ‘lie’ is a crutch. Real journalism is to actually challenge things factually.” (Rutenberg later added: “You don’t want it to feel like name-calling.”)

Baquet also dismissed a question on why the Times devoted a year and a half to coverage of Clinton’s email scandal while Trump lied with impunity:

I actually don’t buy the argument that we created a false equivalency between the email stories and the reporting about Donald Trump. And I think any close reading of the coverage of the two bears that out…I just don’t buy it. I don’t think there was a false equivalency.

(To borrow Times-approved lexicon, that is a falsehood. A 2017 study published in the Columbia Journalism Review found that “in just six days, The New York Times ran as many cover stories about Hillary Clinton’s emails as they did about all policy issues combined in the 69 days leading up to the election.”)

Peter Baker went several steps further:

If you’ve spent years doing this, you train yourself to basically stop thinking like a real person, and to think like a journalist. Some of us choose not to vote. I don’t vote, even in the privacy of a polling booth, because it helps me stay as neutral as possible. In my own mind I’ve never made up whether this person is better than that person for the job. It doesn’t mean I’m not biased — we all are — but that’s how I try.

Maggie Haberman concurred:

It’s the same as Peter — I try really to just basically remove myself from any semblance of real personage.

This is a profoundly dehumanizing, and borderline psychopathic, understanding of the journalistic mission. (It’s also, in Baker’s case, a logical fallacy. His approach implies causation works backwards: “I don’t vote, therefore I don’t have views.” Voting is a product of one’s views, not the cause of them.) In a world where journalism is little more than the robotic recounting of facts, shorn of its power to engender political accountability and stripped of its swashbuckling joie de vivre, politics becomes virtually indistinguishable from sports — a way to while away the time by debating who’s up and who’s down — rather than a contest of society’s values whose outcomes tangibly affect hundreds of millions of people.

Given this blasé outlook, it is no surprise that the press has already begun rehabilitating some of the most corrupt political actors of the past four years. (And why shouldn’t they? If the Times’ chief White House correspondent’s years of reporting haven’t armed him with the knowledge required to choose the better candidate in a voting booth, it’s unclear how his journalism could be expected to produce any more enlightenment.) Axios’ Jonathan Swan — who, like many other names featured in this newsletter, has produced quality journalism as well — devoted an entire ‘episode’ of his post-election series to laundering Bill Barr’s reputation via leaks obviously authorized from Barr himself. Politico ran a highly sympathetic story on Ezra Cohen-Watnick, a former National Security Council aide who participated in the Trump administration’s propaganda efforts to accuse Obama officials of spying on him. Miles Taylor, a senior Homeland Security official who was intimately involved with Trump’s child separation border policy, was transmogrified, however improbably, by a friendly Washington Post profile into a paragon of integrity.

Earlier this month, Washington Post Global Opinions editor Karen Attiah called the press to account for its role in facilitating Trump’s rise:

From the moment Trump entered the 2016 race, endless oxygen was given to his racism and lies. White supremacists were deemed worthy of profiles noting their haircuts and wardrobes or allowed NPR airtime to rank the intelligence of the races. The breaches continued as ex-Trump officials were allowed to profit from distorting the truth to the American people, through TV analyst spots, book deals and Harvard fellowships.

Our media ushered all this through the door, under the aegis of “balance” and “presenting both sides” — as if racism and white supremacy were theoretical ideas to be debated, not life-threatening forces to be defeated.

“The Trump years are over,” Attiah concludes, “but the Fourth Estate cannot rest in complacency.” Based on what we’ve seen in the nearly three months since the presidential election, this appears to be a battle that’s already been lost.