It seems I have developed a sporadic January tradition of skewering Adam McKay movies. Three years ago it was Vice, an angry biopic about Dick Cheney, which I called “an unequivocal catastrophe of a movie.”

I won’t bury the lede: Don’t Look Up is even worse.

The principal culprit is once again McKay’s knee-jerk contempt for his own audience. Back in January 2019, I wrote this about Vice:

His condescension towards the American public is rendered in brief but telling snippets. There’s a slow-mo close-up of young adults in the throes of ecstasy (and, probably, Ecstasy) at a nondescript party, a scene presumably meant to illustrate the apathy of the millennial set in the face of their government’s horrific actions, but which mostly reminded me that there are more enjoyable ways to spend one’s evening than shelling out thirteen bucks to watch a bad movie.

Similarly, a post-credits scene depicts a focus group session that devolves into politically-motivated fisticuffs, at which point one woman turns to another (the American dunces in Vice are all women) and says, “I can’t wait to see the new Fast & Furious movie. It’s going to be so lit.” This is an odd series of objections from the guy who spent the Bush years making movies about mustachioed ’70s-era news anchors, gay French racecar drivers, and a pair of adult step-brothers living with their geriatric parents.

Since then, McKay’s worst instincts have only worsened. Somehow, the more horrifying the subject — Dick Cheney in Vice, the extinction of the human species in Don’t Look Up — the more ham-handed and farcical his portrayal.

For those who haven’t seen it yet, Don’t Look Up tells the story of two astronomers, Randall Mindy (played by Leonardo DiCaprio) and Kate Dibiasky (Jennifer Lawrence), who discover that a massive comet is on a trajectory to collide with Earth in six months, extinguishing all life. Faced with this terrifying countdown, the two proceed to do what any reasonable person would: call the authorities, alert the media, raise awareness.

But their strategy is blunted at every turn by apathy and cynicism. The American president, Janie Orlean (played by Meryl Streep), is more concerned about shepherding her increasingly controversial Supreme Court nominee through the confirmation process than in confronting the imminent obliteration of the planet — the news of which, she worries, may hurt her party in the midterms.

Meanwhile, the hosts (Cate Blanchett and Tyler Perry) of The Daily Rip, a slightly-too-on-the-nose stand-in for MSNBC’s real-life Morning Joe, are (respectively) too sexually enthralled or viscerally repulsed by their astronomer guests to take seriously the looming threat they were invited on the show to discuss.

Despite these setbacks, Mindy and Dibiasky eventually persuade the White House to pursue a credible mission to prevent total devastation. A plan is developed to launch nuclear explosives to “blow Comet Dibiasky off her course.”

But just after the mission gets underway, it is unceremoniously canceled by the president, at which point it is revealed that one of her political benefactors, tech industry CEO Peter Isherwell1 — a disconcerting fusion of Elon Musk’s persona with Christopher Walken’s vocal cadence, in a deft portrayal by Mark Rylance — has discovered the presence of trillions of dollars’ worth of valuable minerals on the comet, whose mining would financially benefit his company, BASH.

And so the sensible, safer mission is replaced with an absurdly risky one tailored towards benefitting corporate interests rather than ensuring a maximal chance of success: use a fleet of BASH space drones to attach themselves to the comet, deploy “microexplosives” to splinter it into 30 smaller meteoroids, and guide them to the Pacific Ocean, where they will be picked up by the U.S. Navy.

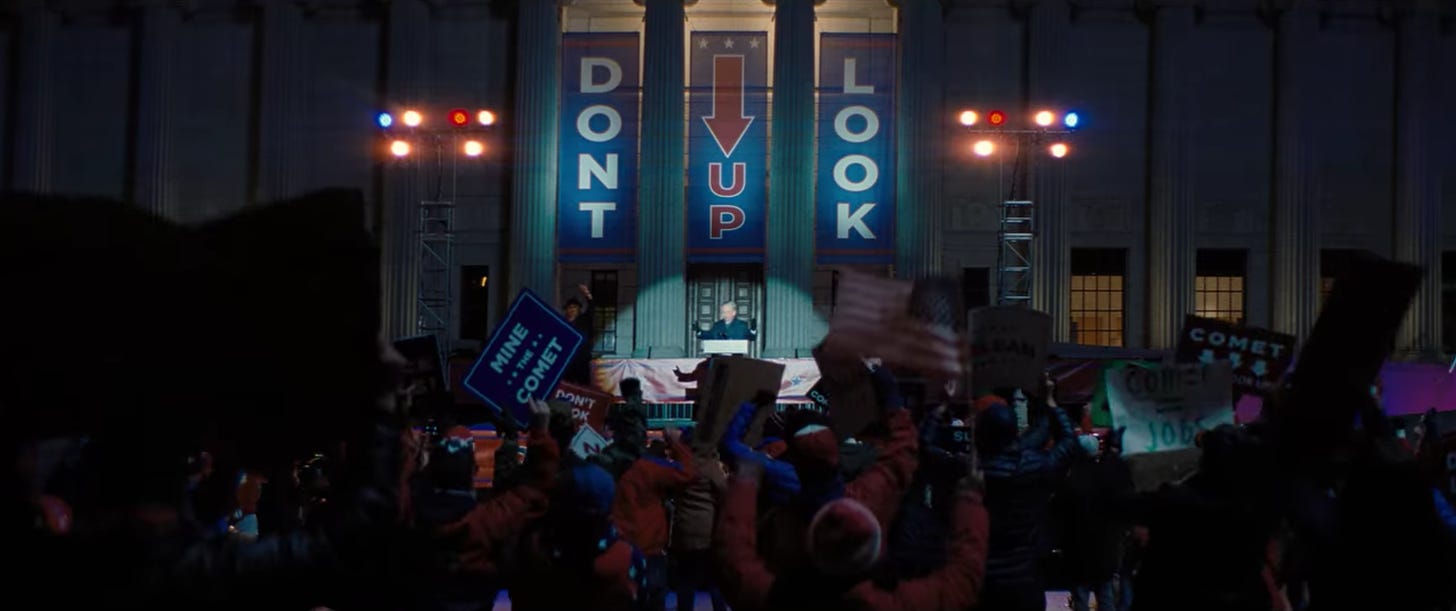

Meanwhile, across TV and social media, the population begins to retrench into familiarly polarized camps. Chastened by a brief dalliance in the halls of power, Mindy rejoins Dibiasky to publicly castigate the White House for its duplicity and corruption, urging the public to “just look up into the sky” and see the comet for themselves. But as political campaign season heats up, “Don’t look up” predictably becomes a countering rallying cry for President Orlean’s rabid fans.

McKay’s portrayal of this aspect of the American cultural milieu manages to rank among Don’t Look Up’s less preachy and most affecting plot points, not least because its cultural doppelgänger has been playing out in realtime every day for nearly the past two years. As New York’s Eric Levitz (in an otherwise harsh review) noted:

Although written before the pandemic, many of its social criticisms feel sharper in 2022 than they would have in 2019. The notion that a threat as immediate and universally menacing as a descending comet could become culture-war fodder — thereby turning the mere act of “looking up” into a litmus test for partisan allegiance — is a bit too plausible at a time when anti-vaxx identity politics has pushed U.S. COVID deaths over the 800,000 mark.

As you’ve probably gathered by now, Don’t Look Up is an allegory for our collectively impotent response to the slow-motion catastrophe that is climate change.

And in case it wasn’t perfectly clear, Adam McKay thinks we’re a bunch of miserable failures. (Hard to argue with that.) We’re so engrossed in our inane morning-show nothingburger controversies — in the film, Ariana Grande and Kid Cudi enthusiastically embrace vapid, Extras-style celebrity alter egos embroiled in a made-for-TV relationship spat — that we can’t be bothered to mobilize to save our own lives.

More importantly, though, Adam McKay is concerned that his audiences won’t grasp how smart he is. So he repeatedly hits us over the head with visual metaphors to ensure we can’t miss it.

Here, for example, is a still from a Don’t Look Up scene depicting the New York headquarters of a certain newspaper2, whose font, I’m sure, is not at all meant to evoke its real-world inspiration:

A similarly heavy-handed treatment engulfs the president and her family. The gauche “Don’t Look Up” baseball cap she wears, the storyline about her scandal-ridden Supreme Court nominee, as well as the entire character of her son and chief of staff Jason (played by Jonah Hill), are designed primarily to remind you of a certain recent occupant of the White House.

As if to underscore the parallels, at a political rally Jason exclaims to the crowd: “Is that a rock-solid ten smokeshow of a president or what? If she wasn’t my mother…" he trails off, in an homage of sorts to Donald Trump’s infamous 2006 interview where he made an almost identical comment about his daughter Ivanka.

What does any of this have to do with climate change? Who knows, really?

Between Vice and Don’t Look Up, it is clear that Adam McKay has lost faith in the American public. This is understandable! There’s a lot to be depressed about. And McKay — whose political passions appear considerably more personal and deeply held than those of most of his show-business peers — is not wrong to pinpoint villains: the struggle to save our planet is among the clearest cases for moral certainty of our (or any future) generation.

The trick is picking the right villains. In one of Don’t Look Up’s cheekier cameos, Chris Evans appears as a movie star dispensing classic political punditry during a promotional tour for his comet-inspired film, Total Devastation: “Yeah, this pin points both up and down. Because I think as a country we need to stop arguing and virtue signaling. Just get along.” False equivalence couldn’t have been expressed any better if Ryan Lizza had written the damn thing in Politico Playbook.

But what’s less understandable is why McKay has determined that mocking his audiences for their cumulative frivolousness represents his best chance at turning things around. As The Guardian’s Charles Bramesco wrote: “McKay is so un-shy about expressing his blanket contempt that one starts to wonder who this could possibly be for.”

In this sense Don’t Look Up is Hollywood’s Mueller Report: either a total catastrophe or the second coming of Christ. (Or, just maybe, neither one managed to make the best possible case without muddying its thesis.) Rolling Stone concluded: “While McKay may believe that we’re long past subtlety, it doesn’t mean that one man’s wake-up-sheeple howl into the abyss is funny, or insightful, or even watchable. It’s a disaster movie in more ways than one.” A different Guardian piece called the film “an A-list apocalyptic mess.” And New York’s Vulture site observed: “McKay…just doesn’t care enough about popular culture or social media to effectively skewer it.”

Even its fans are forced to make strategic concessions. Current Affairs’ Nathan Robinson’s lengthy review concludes: “I have not commented on the quality of Don’t Look Up as a film. But as I said, I think that’s somewhat beside the point.” He continues:

We can imagine, in the world of the film, those concerned about the comet making a film that satirized the lack of national action to stop the comet. And in the world of the film, reviewers simply respond by calling it “heavy-handed,” the director’s “worst film yet,” saying it “misses its targets,” that its humor is too “broad.” Instead of discussing the issues the film raises, they discuss whether the film is good or bad and whether it is successful in the way that it approaches the issues…

A central point made by Don’t Look Up is that when things are matters of life and death, we need to treat them as such. Giving such a film a thumbs-up or thumbs-down and assessing the quality of its humor shows that one has missed the point entirely.

This preemptively defensive conflation — the notion that disliking the film renders you no better than one of the many lemmings portrayed in it — has been parroted elsewhere, most notably by Adam McKay’s Don’t Look Up co-writer, journalist David Sirota:

But this line of reasoning only underscores the critics’ point: if the chief response to viewers rubbishing a movie about climate change is to condemn them as morally equivalent to those apathetic about climate change, then perhaps the real problem was…the movie?

There is ample reason to suspect this. While waiting for Don’t Look Up’s comet to make touchdown and put me out of my misery, I repeatedly thought back to Melancholia, a 2011 Lars von Trier film about a planet headed towards a devastating collision with Earth. Contra McKay’s portrayal of the planet’s final moments — which alternate between harried depictions of grotesque ignorance and the protagonists’ righteous indignation — Von Trier’s ethereal treatment of humanity’s fleeting last breaths continues to haunt me with its realism a full decade later. It’s not always about how loud you shout.

In one of the movie’s rare laugh-out-loud moments, Mindy describes Isherwell to Dibiasky as “the guy that bought the Gutenberg Bible and lost it.”

Incidentally, Don’t Look Up’s cinematic reincarnation of the Times is head-scratching in so many ways, starting with the scope of its employees’ duties. One editor asks his colleagues to set up the astronomers with a pro bono attorney, while another says, in front of Randall Mindy: “Make sure this one gets media training before he hits the shows. He seems a step slow.” The Herald then proceeds to set up the astronomers — who, again, are sources, not journalists! — with an interview on a TV morning news show, The Daily Rip.

Immediately after their appearance on the show, Mindy and Dibiasky are inexplicably invited back to a conference room at The New York Herald’s offices to review a full presentation of web traffic analytics and social media reactions to their TV appearance (“clicks overall were below basic weather and traffic stories”) as well as a collage of notable memes (“Meow! Me likey hunky Star Man”).

I realize I’m just ranting now, but how many weather and traffic stories have you ever read in The New York Times?! It’s enough to make you wonder if Adam McKay has ever picked up an actual newspaper. (Or, to borrow Eric Levitz’s more concise appraisal: “McKay’s conception of the news media’s role, meanwhile, seems slightly deranged.”)

I’m about as vociferous a critic of the Times as they come, but somehow I doubt Dean Baquet has nothing better to do than spend his workday reviewing memes. (Most likely because he’s too busy both-sides-ing the word “lie” at a panel event.)