The con is coming from inside the house

It's reassuring to assume that scammers are confined to the fringes of the crypto ecosystem. They're not.

(Note: Brett Harrison has since deleted *all* of the misleading tweets I referenced below.)

On Thursday, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) sent a cease-and-desist letter to Brett Harrison, the president of the US arm of crypto exchange FTX, one of the largest in the world. The letter noted that Harrison had falsely tweeted that FTX US’s customer deposits were FDIC-insured. They were not.

As the FDIC letter noted:

In fact, FTX US is not FDIC-insured, the FDIC does not insure any brokerage accounts, and FDIC insurance does not cover stocks or cryptocurrency. The FDIC only insures deposits held in insured banks and savings associations (insured institutions), and FDIC insurance only protects against losses caused by the failure of insured institutions. Accordingly, these statements are likely to mislead, and potentially harm consumers….

You shall immediately remove any and all statements, representations, or references that suggest in any way, explicitly or implicitly, that: (a) FTX US is FDIC-insured; (b) any FTX US brokerage accounts are FDIC-insured; (c) any funds held in cryptocurrency or other financial products…are or can be protected by FDIC insurance; or (d) FDIC insurance provides protection or coverage in any manner or extent other than those set forth in the FDI Act…

Harrison explained himself on Twitter the next day:

Sam Bankman-Fried, the founder and CEO of FTX, followed up as well:

But neither of their tweets is true.

Harrison’s original tweet, the one the FDIC told him to delete, read:

This tweet is about as clear as it gets. It is virtually impossible to read it and conclude, as Harrison later described, that “we didn’t suggest that FTX US itself…benefit from FDIC insurance.” Indeed, the tweet very explicitly states that FDIC insurance applies to customers’ direct deposits on FTX US. That is, of course, false.

On the very same day, Harrison went even further:

This is also false, but even bolder: Harrison not only claimed the individual customer (as opposed to FTX itself) is the beneficiary of FDIC insurance, but also implied that the FTX T&Cs — which correctly noted that individual FTX customer accounts were not FDIC-insured — got this wrong. (They didn’t, and he did. Those unchanged T&Cs are still in effect today.)

It would be one thing — albeit a pretty staggering level of incompetence in its own right — if the president of FTX US made an honest mistake and somehow failed to understand that the financial entity he runs wasn’t FDIC-insured.

But that doesn’t appear to be the case, because he also tweeted about FDIC insurance a week later, in another tweet that (for whatever reason) the FDIC did not explicitly mention in its letter, and which is still live online:

It is in this thread that you can glimpse just how sordid and unethical FTX’s public communications are. Harrison tweets about a new product release, FTX Stocks, and is immediately asked by a user (@ath33) whether the product is FDIC-insured.

Keep in mind that there is only one possible way to reasonably interpret the user’s question: (s)he’s obviously asking whether FTX US customers’ funds are FDIC-insured. That is, if something were to happen to FTX US, would the FDIC reimburse users of the new FTX Stocks product for their cash holdings?

But Harrison responds with a deliberately misleading bait-and-switch: he writes that “cash associated with brokerage accounts is managed into FDIC-insured accounts at our partner bank.”

This is irrelevant. FDIC insurance exists to protect customers of a bank from the collapse of that bank. As the FDIC cease-and-desist letter states, “FDIC insurance only protects against losses caused by the failure of insured institutions.” That is, if I deposit up to $250,000 of my own money in an FDIC-insured bank, and that bank then goes bankrupt, I am entitled to receive my entire deposit back.

This is what the Twitter user was asking about. But Harrison’s response subtly conflated FTX US customers with FTX US itself. His tweet noted that cash held by FTX US on behalf of its customers was itself deposited in an FDIC-insured bank. That is, FTX US as a company is the customer of an FDIC-insured bank. But this has absolutely no bearing on the person’s question: all this means is that FTX US is entitled to FDIC reimbursement in the event that its own partner bank goes bankrupt.

Of course, this insurance does not apply to FTX US itself going under. (Imagine if the FDIC, or its member banks, were on the hook for reimbursing each of its customers’ customers.) It only comes into play if FTX US’s partner bank goes bankrupt. And anyone, most of all Harrison, would understand that the user was obviously asking about FTX US’s insurance, not its partner bank’s.

In other words, Harrison replied to a very clear query about whether FTX US users’ cash was protected from the failure of FTX US by answering a different question entirely, but in a way designed to look like he was responding to the original one. And in so doing, it becomes difficult to escape the conclusion that he does understand the difference between FTX US’s deposits in a partner bank being FDIC-insured (which they are) vs. an individual FTX US customer’s deposits being FDIC-insured (which they aren’t).

Who cares?

Or, why should a seemingly esoteric Twitter exchange on FDIC insurance matter to anyone?

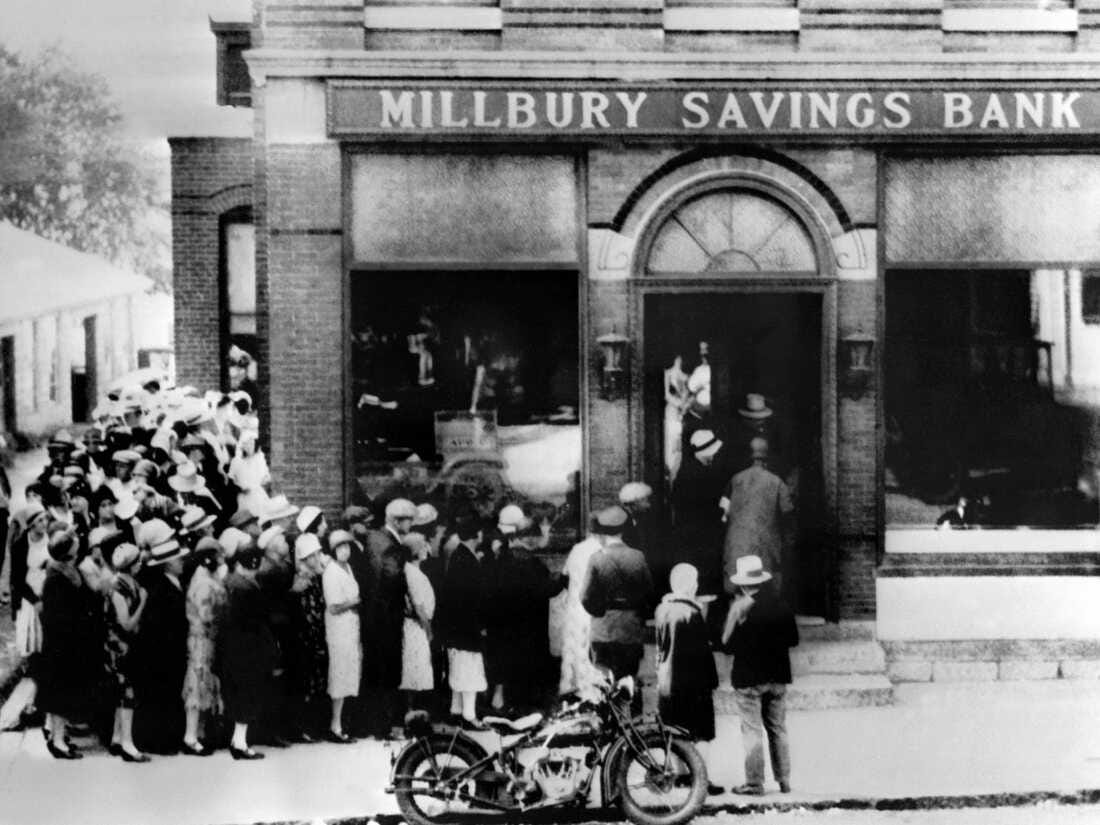

First, it’s important to remember how the FDIC came about. It was established in 1933, in the depths of the Great Depression, following a slew of bank failures that had devastated ordinary citizens across the country. Bank runs (like the one pictured in the photo at the top of this post) were distressingly common: a rumor would spread that a bank was in trouble or going insolvent, and desperate crowds would form outside the bank doors as depositors rushed to withdraw their money before the bank ran out of cash.

This was a bad system, and the advent of FDIC insurance largely fixed it by insuring customers’ deposits at insured banks for up to a set amount of money (which is now $250,000). This government backing effectively ended bank runs for normal customer banking accounts, and the FDIC logo on a bank web site is akin to a stamp of approval declaring “Your funds are safe here.”

So when crypto companies mount a deliberate communications strategy of conflating their own funds at FDIC-insured banks with their customers’ non-FDIC-insured funds on their platforms, they are effectively committing fraud1 by appropriating the patina of security associated with FDIC insurance to a scenario where it doesn't apply. And the consequences of this scam -- end users thinking their funds are safe and risk-free when they very much aren't -- can be enormous.

In fact, this wasn’t the first time in recent days that the FDIC has had to issue a cease-and-desist notice to a crypto company over false or misleading claims. Late last month, the FDIC and the Federal Reserve Board issued a joint statement “demanding that the crypto brokerage firm Voyager Digital cease and desist from making false and misleading statements regarding its FDIC deposit insurance status and take immediate action to correct any such prior statements.”

Here is how Voyager had described FDIC insurance on its web site’s home page:

And on its Twitter feed:

And on its Medium blog:

These lies had very real consequences. When Voyager filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy, scores of its customers falsely believed their funds were insured when they in fact were not:

One customer wrote to the judge in Voyager’s bankruptcy case (per Yahoo! Finance): “I have been in shock since Voyager halted withdrawals. It is as if your bank is no longer allowing you to withdraw from your savings accounts. How would you feel? Would you not feel betrayed?”

In fact, Voyager’s incorrect FDIC language caused so many of its customers to reach out to its partner bank (Metropolitan Commercial Bank) asking about FDIC insurance2 that the bank had to issue a public notice on its web site explaining that its FDIC insurance didn’t cover lost funds due to Voyager’s failure:

Metropolitan Commercial Bank is a New York-chartered bank and member of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. Voyager customer funds held by Metropolitan Commercial Bank are insured by the FDIC up to the maximum amount of coverage per depositor under federal law. The standard FDIC insurance coverage amount is currently $250,000 per depositor for each account ownership category.

FDIC insurance coverage is available only to protect against the failure of Metropolitan Commercial Bank.

FDIC insurance does not protect against the failure of Voyager, any act or omission of Voyager or its employees, or the loss in value of cryptocurrency or other assets.

The crypto world is awash in these sorts of misrepresentations and scams. I have previously covered FTX’s sketchy handling of Tether on its platform: treating it as safe enough to list on FTX and defending its integrity on podcasts, etc., but not trusting it enough to promise 1:1 dollar redemptions for FTX customers:

But other examples abound. Do Kwon built a so-called algorithmic stablecoin (also listed on FTX) that was supposedly pegged to the U.S. dollar but instead collapsed spectacularly and cost its users $40 billion in direct value.3 Celsius famously urged its users to "unbank yourself"4 and repeatedly assured them that their deposits were safe and low-risk before filing for bankruptcy last month, upending countless customers’ lives:

It’s tempting to consider these bad actors as outliers, but this is an increasingly difficult proposition when the president of one of the world’s largest crypto exchanges persistently misleads his own customers and then, when ordered to stop by the FDIC, lies about what he has written.

I’m not a lawyer, so I mean this in the conventional / dictionary understanding of fraud (“wrongful or criminal deception intended to result in financial or personal gain”), as opposed to making a specific legal claim, which is beyond my expertise.

There is, of course, an astronomical irony to the fact that so many crypto believers immediately rushed to beg the U.S. government for a rescue when their libertarian fantasy of government-free finance blew up in predictable fashion. But I digress.

The indirect costs were much, much higher. The collapse of Terra/LUNA sparked a cascading series of falling dominoes: it was the proximate cause of Three Arrows Capital’s collapse, which in turn ensnared Celsius and others.

To Celsius’ credit, this marketing slogan turned out to be fairly accurate.