Tfw your tech startup accidentally becomes the government

Last year I read John Carreyrou's investigative nonfiction book Bad Blood: Secrets and Lies in a Silicon Valley Startup. One theme that Carreyrou returns to numerous times is the fact that Elizabeth Holmes' medical tech startup Theranos consistently made bold proclamations -- to investors, employees, board members, and clients -- about its core product's capabilities that were wildly optimistic, with the hopes that eventually reality would catch up to the marketing hype. In one of many such passages, Carreyrou paraphrases a Theranos employee's thoughts: "This was not a finished product and no one should be under the impression that it was."

Carreyrou is a two-time Pulitzer Prize winner and I can't recommend Bad Blood enough. But strangely, as I read the book I was repeatedly nagged by the same recurring thought: making bold promises about product features that don't yet exist, in the hopes that they eventually will, is precisely what every tech company does. (Indeed, the trope of engineers and product people visibly wincing as a salesperson promises the moon to a prospective client is a tech cliche.) Every company I've worked for in ad tech has, to varying degrees, promised products we haven't yet released on a combination of blind faith and the quarterly roadmap. (The same logic governs internal goal-setting. Google, for example, suggests 60-70% achievement of OKRs is the "sweet spot.") In this specific sense then, there is actually nothing unique about Theranos.

What does make Theranos different, however, is the field it was in: medical technology. The company promised that it could run a battery of medical tests using only a single drop of blood from a patient's finger, a claim with the potential to revolutionize healthcare: patients could take the blood testing machine home with them, beam the results back to their doctors, and never even have to bother with in-person doctors' visits in some cases. When Theranos' claims proved illusory, the potential consequences were horrifying: false positives could (and did!) convince patients they were in dire health when they weren't, prompting emergency-room visits. Unlike so many other star-crossed startups who fell short of realizing their lofty objectives in areas like photo sharing, co-working spaces. and fitness wearables, Theranos' failures came with the unmistakable gravity of potentially life-altering repercussions.

I bring this up because one of the unspoken questions in American politics and culture today is whether Facebook is more like other societally inconsequential tech companies that are iteratively fudging their way towards better outcomes -- moving fast and breaking things, as it were -- or whether it's more like Theranos.

This is not a comparison I've seen made elsewhere, in large part because so much of the public conversation around Facebook is narrowly tactical: should they or should they not, for example, ban lying in political ads? (Elizabeth Warren is a notable exception.) And yet the localized answers to these types of questions accomplish little in moving the needle on a core underlying fact: Facebook has built an ersatz government all its own. The question is whether this threat is acute enough to represent a large-scale Theranos -- endangering the public health, psychologically if not physically -- or something smaller and more manageable, more like the thousands of other tech companies that have overpromised and underdelivered.

The latest event to spark debate is Facebook executive (and Mark Zuckerberg confidant) Andrew Bosworth's internal post arguing for a hands-off, laissez-faire approach to political speech on the platform, as the country gears up for the presidential election this November. In his now-famous blunt style, Bosworth makes a number of bold statements, including that Facebook ads were responsible for Donald Trump's victory and that "social media is likely much less fatal than bacon" (emphasis mine). But perhaps most startling from my viewpoint was his almost casual discussion of what prevents him -- and, by extension, Facebook -- from tweaking platform policies and algorithms to reduce the chances of Donald Trump's reelection:

As a committed liberal I find myself desperately wanting to pull any lever at my disposal to avoid the same result. So what stays my hand?

I find myself thinking of the Lord of the Rings at this moment. Specifically when Frodo offers the ring to Galadrial and she imagines using the power righteously, at first, but knows it will eventually corrupt her. As tempting as it is to use the tools available to us to change the outcome, I am confident we must never do that or we will become that which we fear.

What's most alarming about this section isn't the specific decision he arrives at in relation to Facebook's policies on misinformation. (That decision is grounds for an entirely separate discussion.) It's that using Facebook's enormous cultural and technological preeminence to influence an election isn't merely considered, but is implicitly assumed to be well within its power to achieve. As Mark Zuckerberg has said, "In a lot of ways Facebook is more like a government than a traditional company."

This reality is reinforced by a quick perusal of Facebook's official corporate releases. I subscribe to an email feed of Facebook bulletins, and in recent months the headlines have been a relentless drumbeat of dystopian fare. "Helping to Protect the 2020 US Elections." "Helping to Protect the 2020 US Census." "An Update on Building a Global Oversight Board." These quasi-governmental missives are not the run-of-the-mill corporate updates of yesteryear's economic behemoths, to say the least.

That last headline, especially, hints at one of Facebook's many internal contradictions. In November 2018, Mark Zuckerberg kicked off discussions about a Facebook-spawned oversight board -- a Supreme Court of sorts -- that will eventually determine what can and cannot be posted on Facebook, explaining: "I've increasingly come to believe that Facebook should not make so many important decisions about free expression and safety on our own."

Establishing a global oversight board to police content on Facebook's platforms represents a recognition that today's Facebook, as Zuckerberg concedes, is ill-equipped to make such far-reaching decisions. (It is also almost certainly a governance sleight-of-hand: while the board is ostensibly independent, its budget will nevertheless rely on continued funding from Facebook.)

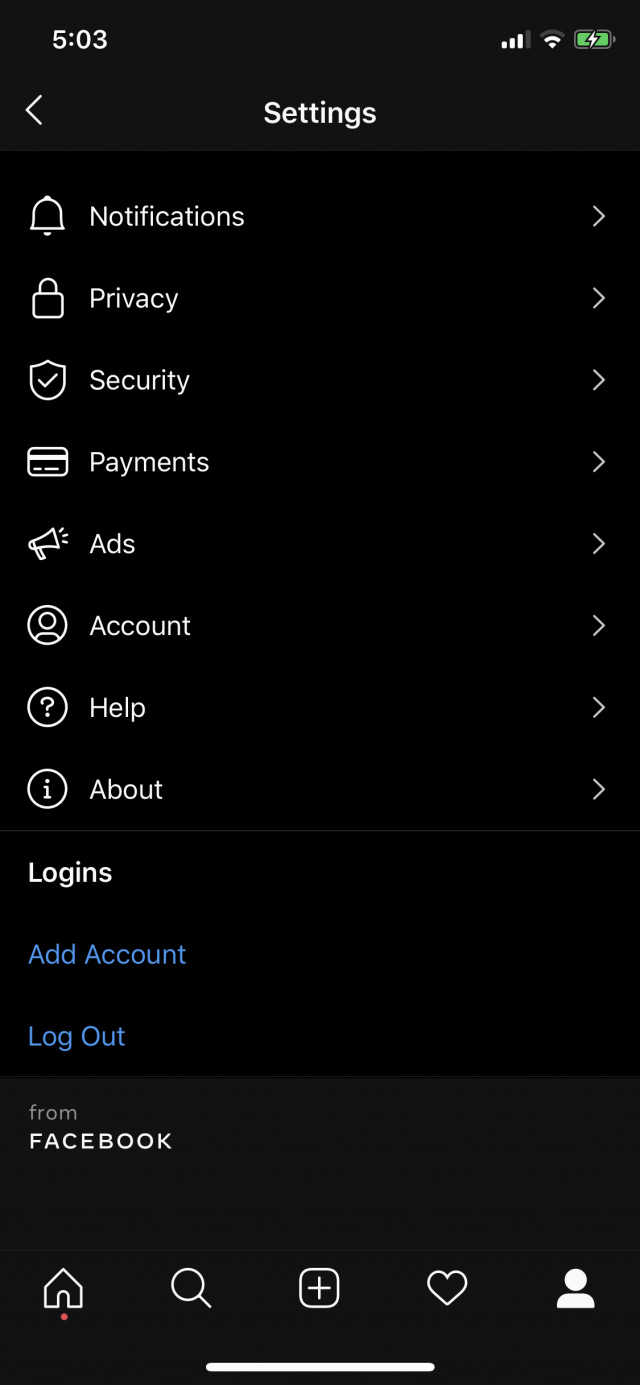

And yet the board will be performing an inescapably regulatory, near-governmental function at the same time that its corporate patron is rapidly attempting to integrate its disparate acquisitions' messaging back ends (a solution otherwise in search of a problem), in order to stave off actual regulatory action that could culminate in Facebook's breakup. ("You can't break us up! We're functionally inseparable!" - Microsoft, 1998.) And if you've started to notice the rather ham-handed "from Facebook" tag appearing in your Instagram and WhatsApp mobile apps, well, this is no coincidence either:

All this to say: when Bosworth writes that "I expect...that the algorithms are primarily exposing the desires of humanity itself, for better or worse," he is casually eliding his company's unparalleled power to shape those desires. As Alexis Madrigal aptly summarized: "The problem for Facebook, in that regard, is that it created the entire system. The history is its history...It’s silly to say you can’t change the way a river flows when you are the watershed." More to the point from The Margins' Ranjan Roy: "This is the very definition of a need for regulation. By its own admission, the company is acknowledging its unnatural power...The issue is simply its size. An individual, for-profit corporation should not get to decide whether democracy will work."

Part of the public's lingering dissatisfaction with Facebook's every policy move, then, is best understood as a non-verbalized expression of despair at our options: perhaps the problem is not whether Facebook chose A or B, but that it's in a position to make these decisions at all.