NFTs and Nomar

True believers have transformed boring old ownership into something that's alluring, convenient, and lucrative - but also, perhaps, an elaborate con.

Everyone these days is talking about non-fungible tokens, or NFTs. Fred Wilson is talking about it. Alex Danco is talking about it. Chris Dixon at Andreessen Horowitz is talking about it. Reuters is talking about it. Li Jin and Nathan Baschez are talking about it. Benedict Evans is talking about it (at least I assume so: he blocked me on Twitter). Grimes is rolling in it.

So what the hell is an NFT? It’s…hard to explain, and I’ll be the first to admit that — after whiling away several hours this weekend reading up and trying to get my head around it — there’s still at least a 20% chance I’ve misunderstood the concept entirely.

Like most confusing things these days, it has to do with blockchains.1 But first: a non-fungible token (NFT) is to be distinguished from a fungible one — like bitcoin, for example. One bitcoin is fungible with all other bitcoins because they’re all completely interchangeable and worth exactly the same amount.2

An NFT, by contrast, is a token representing a unique, singular artifact. Say you’re a digital artist, and you come up with some weird/exotic/interesting/distressing piece of art:

I mean, sure, ok.

So let’s say you want to sell it. Now, this one above is more or less just a GIF (pronounced jif), but don’t let the simplicity fool you: it just sold last month for 2.20 ETH (ether), or $3,257.72.

The sale was registered on a public blockchain, an immutable ledger consisting of transaction logs that provide definitive evidence of ownership — in the case of the above piece of art, it’s now owned by some guy named @rudy. Once someone like @rudy has bought a piece of digital art, he can turn around and resell it if he wants to — another transaction that will be forever immortalized3 on the blockchain as permanent proof of the change of ownership.

But you’re not limited to selling a single instance of your work of art. It’s digital, right? So it’s infinitely copy-able — meaning you can sell more than one of the same thing, sometimes for a lot of money each, and they’re all considered “originals.” How many originals there are is up to you. According to Crypto Slam, which tracks reseller transactions of “crypto collectibles,” a product called “NBA Top Shot” has accounted for a whopping $242 million in crypto collectible sales in just the last thirty days alone.

NBA Top Shot, per its site, “lets you build a collection featuring all the [NBA] players you love…When you build your NBA Top Shot collection, you get to own and show off the highlights that matter.” For example, for reasons beyond my ability to explain, I am the proud owner of this “moment” featuring Oklahoma City Thunder wing Hamidou Diallo dunking on the New York Knicks in January. There were only 12,000 instances “minted” of this particular moment, and I have one. The moment consists of a brief online video of his dunk shot from several angles, followed by a panel displaying the game’s final score and the date. This “moment” cost me $75.

Now wait a minute, you ask. Can’t you just go to YouTube, type in “hamidou diallo dunk knicks,” and watch the exact same play anytime you want, for free?

I mean, yeah. You could do that.

WTF NFT

That $75 dunk? That was cheap. Last week some dude named @YoDough picked up a LeBron James “moment” for…$208,000. And how do I know this, you ask? Because NBA Top Shot shared the exact same video moment on the extremely free web site twitter dot com:

That’s right: click on it. You just watched a $208,000 piece of art.

It’s not yours, though. It’s @YoDough’s. (Also, $208,000 apparently isn’t enough to cover the audio track.)

It gets weirder. I recently found myself perusing NBA Top Shot’s Terms of Service.4 Turns out, embedded deep into the legalese is Section 4, Part B (several clauses below bolded for emphasis). As a recently minted Top Shot owner, I thought Paragraph 1 started out quite promisingly:

You Own the NFT. Each Moment is a non-fungible token (an “NFT”) on the Flow blockchain. When you purchase a Moment, you own the underlying NFT completely. This means that you have the right to trade your NFT, sell it, or give it away.

But then things took a dark turn in paragraph 2:

For the sake of clarity, you understand and agree: (a) that your purchase of a Moment, whether via the App or otherwise, does not give you any rights or licenses in or to the DLI Materials (including, without limitation, our copyright in and to the associated Art) other than those expressly contained in these Terms; (b) that you do not have the right, except as otherwise set forth in these Terms, to reproduce, distribute, or otherwise commercialize any elements of the DLI Materials (including, without limitation, any Art) without our prior written consent in each case, which consent we may withhold in our sole and absolute discretion…

At this point I’m slightly twitching, glancing alternately at my sweet, sweet Hamidou Diallo moment and then back at that $75 debit to my bank account. “I own the NFT completely,” I shout to no one in particular. “It says it right there in Paragraph 1!” Surely, I reassure myself, surely the recurring and ominous references to “Art” in this dystopic, Orwellian paragraph 2 must mean something innocuous, right? Right?

Replied the Terms of Service:

“Art” means any art, design, and drawings (in any form or media, including, without limitation, video or photographs) that may be associated with a Moment that you Own.

Wait.

Wait.

What exactly do I own here? You’re telling me I paid $75 (or 1/2,773rd of a LeBron dunk) for a digital crypto-token that says I “own” a moment for which — if I actually re-uploaded the underlying video to YouTube — I would almost certainly be served a DMCA takedown notice from the National Basketball Association for copyright infringement? Are you $%!@%$ kidding me?!

How is this not the most obvious, ridiculous, bullshit con of all time?

Take me out to the ballgame

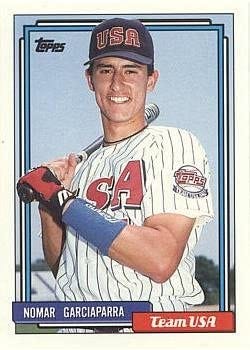

Well, because of this:

This, my friends, is Nomar Garciaparra.

Nomar (so named because it was his father, Ramon’s, name reversed) was my childhood hero. For a kid growing up just a couple T stops away from downtown Boston in the late 1990s and early 2000s, Nomahhh was the zenith of cool: a shortstop with the arm of a cannon and the plate discipline of Vladimir Guerrero playing baseball for a town with a chip on its shoulder precisely the size and shape of New York.

So how popular was Nomar Garciaparra in Boston, Massachusetts? I’ll put it this way: the first time I became aware of Mambo No. 5 was literally when a Boston-area radio station released a version with Red Sox lyrics and called it Nomar No. 5 (his jersey number).5

To this very day, on those rare occasions I find myself in a batting cage6, I still subconsciously mimic his toe-tapping, glove-adjusting, bat-wielding OCD ritual:

And as a Red Sox fan in the 2000s, I collected baseball cards. Lots and lots of baseball cards. Thousands of them, in fact. In a stroke of luck, our tiny Boston-adjacent town was home to a sports souvenir and collectibles shop called Sportsworld.7 Over the years, thanks to Sportsworld and eBay, I soon became the owner of well over a hundred individual baseball cards of Nomar Garciaparra. Thanks to this collection, almost two decades later I can still recite several seasons’ worth of consecutive Nomar batting averages by heart without looking: .306, .323, .357, .372. (It gets less impressive after that. Thanks, Sports Illustrated curse.)

But that Topps 1992 Team USA Nomar Garciaparra rookie card was my white whale. Priced at around $100 or so, it was galaxies outside my budget, but I scoured eBay for it relentlessly anyway, searching futilely for affordable versions in “Mint” or “Near-Mint” condition.

Why did I want that card so desperately? For one, because it was an official “rookie card,” a designation bestowed on it by the monthly card pricing magazine Beckett Baseball, which was consulted religiously by the collector community. But also, I wanted it because it was rare and, therefore, valuable. Not in the financial sense, even, but in terms of how excited I would have been to own one.

Slight detour here: the world of sports trading cards is actually quite fascinating, even if you care nothing for sports. A New York Times article two weeks ago featured a collector whose two LeBron James cards are together valued at over $7 million: the article’s main photo features the collector, his cards, and an armed security guard standing at attention in the background.

More to the point, the Times explains just how vulnerable the sports trading card market is to supply shocks:

Scarcity has always driven the resale prices of cards, but in the mid to late 1980s, as the hobby morphed into a lucrative business, speculative collectors began buying cards of promising baseball prospects in bulk — Gary Sheffield, Gregg Jefferies, Todd Van Poppel, to name a few — hoping each one would turn into the next Mantle rookie card.

In order to meet that demand, card companies like Topps, Donruss, Upper Deck, Fleer and Bowman overproduced the cards, which flooded the market. Today, many of those cards are effectively worthless.

“The ’80s and ’90s are known as the junk wax era,” Ivy said. “Nothing was scarce, nothing was rare.”

But in 2003, Upper Deck made a singular rookie card of James under its Ultimate Collection imprint. That card — the one Davis bought in 2016 — contained the N.B.A. logo from James’s jersey, and James signed the card under a photo of him in his crimson Cavalier jersey. It has “1 of 1” written on the card and no other version exists. Packs of that series were sold in some retail shops at the time for $500 or more, and that James card is considered among the most prized in the world.

“I know some people out there who are trying to hunt whales,” Davis said. “I have LeBron’s whale, the only one that someone could ever get.”

The value of a given card, in other words, is quite closely related to how rare it is. But that rarity is totally arbitrary. The card companies control it. There’s no physical limitation preventing them from printing more cards at any time. And so presumably every season they have to make a calculation about what will maximize their expected return: printing more cards to make a quick buck, thereby flooding the market and inaugurating another “junk wax era?” Or printing a limited run, perhaps losing some revenue up front in exchange for a galloping secondary market that, over the long term, conjures up heightened allure and sexy New York Times profiles, thereby elevating the value of the hobby overall?

This is, not coincidentally, the same dilemma confronting NBA Top Shot. As mentioned, my Diallo dunk is one in a series of 12,000 identical instances NBA Top Shot “created” of the same moment. That’s one of the reasons it cost “only” $75. That $208,000 LeBron James moment, however, was one of just 49.

In other words, NFTs generate value out of artificial scarcity the same way Topps or Upper Deck or Bowman do. So why does paying $75 for a basketball dunk video feel so absurd, perhaps even borderline fraudulent, while dishing out orders of magnitude more money for a physical card is just fine?

Imagine I generated an incredibly high-res scan of that single-edition Lebron James Upper Deck rookie card, the one worth millions of dollars, and then I figured out which print shop they used to produce it, and made a new copy using the exact same printers as the original. I think everyone would agree that, despite being literally identical in every conceivable aspect, this new card would be effectively worthless.

But why?

But your picture on my wall: it reminds me that it's not so bad, it’s not so bad

I think it has something to do with fandom. Being a fan, or even a stan (as the kids say these days), brings with it a set of obligations and concomitant benefits. The obligations vary widely: if you’re a fan of a particular band, you likely buy merch from their online store, contribute to their Patreon (if one exists), and attend their shows whenever they tour in your city. Maybe you even join quasi-cult-like online communities, call yourself an “Army,” and post endless memes to hijack right-wing Twitter hashtags:

But with these obligations come some pretty sweet benefits as well. (It’s the inverse of that Spiderman line: with great responsibility comes great power.) You introduce your friends to your favorite band’s music and earn immense, almost unspeakable satisfaction when they become just as obsessed as you are. You develop weirdly specific memes and increasingly convoluted in-jokes. You start to accumulate an absurdly detailed “knowledge graph” of everything related to your objects of fandom: you know each band member’s personality quirks and idiosyncrasies, which ones are good dancers (trick question: all of them, obviously), and which ones have creepy smiles:

Oh hey there.

Every fandom has, you might say, its own extremely specific set of rules. For card collectors, the fact that the single-edition LeBron James card can theoretically be copied doesn’t alter the fact that the one officially issued by Upper Deck is the only “true” one in existence, even if my counterfeit duplicates are quite literally and technically identical. If Upper Deck had issued five LeBron cards instead of one, each of those five would be considered authentic (although each would probably be worth substantially less than the single one that exists today), and anything else wouldn’t be. That’s just the rule.

The value, then, is derived from a social contract. The card is valuable because we all agree it is. The initial bubble may have been propped up by true believers alone — people sufficiently invested in the concept to intuitively grasp the distinction, perhaps invisible to outsiders, between a genuine card and its perfectly identical doppelgänger — but the rules have now marinated for long enough within broader societal consciousness to sustain a robust and lucrative sports trading card market. You, as someone who’s not remotely interested in sports, may not have any clue why two Lebron James cards are worth $7 million, but you nevertheless accept that is the fair value for them. This general process is, by the way, also how money works.8

So where does that leave NFTs? Well, different flavors of NFTs — whether they’re CryptoKitties or Top Shots or other forms of digital art — have their own fan clubs too. (The cryptokitty “Pudding Daintydot” is currently on sale for $1 million.) And those fan clubs have their own sets of rules, however arcane or esoteric they may appear to outsiders. But do these fan clubs have staying power? Does the $242 million in Top Shot reseller transactions over the past month represent a lasting breakthrough?

It’s hard to say. Part of me thinks NFTs are the Google Glass of collectibles: their value is severely diminished by their social awkwardness.

If you think of coolness as the marginal value of an entity’s ineffable “brand,” Google Glass landed at approximately zero. Even that most mainstream of devices, the iPhone, has a coolness premium. Apple doesn’t sell them at cost: it sells them at ridiculous markups because you are, in a sense, paying for the enhanced social status the iPhone confers on you. Another version of coolness: having seen a now-hugely popular musical act ten years ago in some Bushwick dive bar back when they were nobodies. It all says something about your taste. Google Glass might be the inverse: if anything, it imposes a social cost and may be worth less than its component parts.

Are NFTs cool? Maybe. Or maybe they’re ridiculous. Maybe they’re nothing like baseball cards because, as my friend explained to me: “The pleasure one gets from sitting on the floor with a pile of cards can't be replicated by an NFT…I think the physicality of the cards was essential." As one digital artist explained to The Guardian:

If you look at an NFT entry, it’s just a hash, a string of numbers and letters, and doesn’t let you view the art itself. It takes the worst of the high-end art market – works sitting around in air-conditioned warehouses in ports, being speculated on but never actually being looked at – and makes it a thousand times less ecologically friendly.

On the other hand, who am I to tell @YoDough that his $208,000 LeBron dunk isn’t special? As Benedict Evans points out: “People do trade baseball cards, photographs, and oil paint smeared on cloth with no intrinsic value, and perhaps this is a new kind of creative and exchangeable artefact.”

It’s true, as its critics might charge, that owning an NFT isn’t so much owning a “thing” as it is owning a reference to a thing. It’s Patreon, on a blockchain, for imaginary products. And yet value is often defined by references, or associations, to other things: would George W. Bush have been a plausible elected official without his famous father? Would a lock of hair from my head be worth the same as one from George Clooney’s?9 Why did a baseball which retails for under $10 sell for $752,467.20 simply because it was the 756th one to be launched into orbit off the bat of a man named Barry Bonds?

And here’s the other thing: no one owns anything anymore. We used to buy big, heavy hardcover books. We collected vinyl records, and then tape cassettes, and eventually CDs and DVDs. We downloaded MP3s from apps with names like Napster and LimeWire and Kazaa, and stored them on external hard drives. We either purchased or rented VHS tapes from Blockbuster, where every movie we selected meant that it was, for a brief moment, ours alone: no one else could rent that same copy at the same time.

Now? We subscribe to Netflix, stream music and podcasts on Spotify, download DRM-protected books to our Kindle, watch TV shows on Hulu. We upgrade to the latest iPhone by leasing it from our telecom provider. We rent others’ spare bedrooms, or a ride in their cars, or just their cars, or just them. Much of our consumption draws from theoretically unlimited resources with zero marginal costs: it’s easier now than it’s ever been to produce and (especially) distribute culture. And yet we, the public, own so much less of this culture now than we did in the days of Blockbuster.

These companies reel us in with their low monthly subscription fees and keep us loyal by persuading us that we’re the recipient of all the benefits of ownership with none of the associated costs. But every now and then the facade drops, and the reality of our rentable lifestyle is blindingly revealed. As these moments go, it’s hard to top the on-the-nose factor of this one, from 2009:

In George Orwell’s “1984,” government censors erase all traces of news articles embarrassing to Big Brother by sending them down an incineration chute called the “memory hole.”

On Friday, it was “1984” and another Orwell book, “Animal Farm,” that were dropped down the memory hole by Amazon.com.

In a move that angered customers and generated waves of online pique, Amazon remotely deleted some digital editions of the books from the Kindle devices of readers who had bought them.

So much for digital ownership.

Conversely, right now I’m staring at my hardcover edition of Kazuo Ishiguro’s brand-new novel Klara and the Sun. It arrived from Amazon yesterday but, unlike those digital editions of 1984, no one can take this one from me. It’s not DRM-protected, it can’t be remotely erased over an Internet connection, it doesn’t require the use of a wifi- or 4G-enabled device to read. It’s a self-contained, physical entity. Like a baseball card.

Or, maybe, like an NFT. Or even bitcoin. Remember, the NF stands for “non-fungible,” but the most popular fungible token in the zeitgeist, bitcoin, stemmed directly from the same underlying ownership paranoia as its non-fungible offshoot. Here’s an excerpt from the original bitcoin whitepaper published in 2008 by the pseudonymous Satoshi Nakamoto:

Commerce on the Internet has come to rely almost exclusively on financial institutions serving as trusted third parties to process electronic payments. While the system works well enough for most transactions, it still suffers from the inherent weaknesses of the trust based model. Completely non-reversible transactions are not really possible, since financial institutions cannot avoid mediating disputes…With the possibility of reversal, the need for trust spreads.

The very next year, Amazon remotely deleted 1984 from users’ Kindles. The promise of bitcoin, then, was that this type of chicanery is simply not possible on the blockchain: a public, immutable ledger consisting of all the bitcoin transactions ever conducted in history, right out there in the open. The Federal Reserve can’t simply produce more bitcoins, like it can with dollars, and thereby devalue it — in fact, no one can.

When so much of our life is borrowed or rented instead of owned, even the smallest immutable claim of ownership — like a cryptographic private key that grants the holder nothing at all except the ability to transfer the value of that key to someone else — can feel realer than it otherwise would. We’re the proverbial Neil Armstrong planting our small American flag on the moon. Except the flag is just a Hamidou Diallo dunk from January, a digital video of something that happened months ago an ocean away. But I own it, whatever “it” is. And that’s something you just can’t put a price on.

But if you really insist on doing so, I’m sure it’s somewhere north of $75.

Although there are many definitions of blockchain, the one I personally subscribe to is: “A much easier way to teach libertarian STEM grads the history of finance (via firsthand reinvention) than simply forcing them to read Debt: The First 5,000 Years.”

Somewhere between $0 and $50,576.51, roughly.

At least until sometime later this year when everyone’s been vaccinated, no one remembers NFTs anymore, and the blockchain people cut their losses amid mounting AWS bills.

So no, I wouldn’t say the pandemic has had any noticeable impact on my social life or hobbies, why do you ask?

I just spent about half an hour trying in vain to find the audio anywhere online: the song was written and produced by 105.7 FM’s (WROR) Tom Doyle, but all I’ve been able to come up with is a different Red Sox remake of Mambo No. 5, along with several other forlorn, nostalgic Bostonians futilely attempting, like me, to recapture the magic. Oh, and a LiveJournal (!) with the lyrics:

A little bit of Pedro to win a game

A little bit of Ramon to do the same

A little bit of Daubach to hit the wall

A little bit of Wakefield's knuckleball

A little bit of Valentin, he's been great

A little bit of Varitek behind the plate

A little bit of Troy hittin' in the stands

But Garciaparra, he's my man

My most recent visit to one, late last summer atop an East London rooftop, culminated in me spending the next three days in a neck brace after apparently pulling a muscle neither I nor my spinal cord were aware I still had.

The shop has since moved from Everett to Saugus, but its proprietor — a legendary guy named Phil Castinetti who wore a conspicuous Yankees hat at all times in a town for which this was nigh unto a criminal act — was unfailingly generous and friendly to my little brother and I, who would traipse into his shop multiple times a week, march right past the expensive autographed bats and baseballs and straight to the cheapest packs of cards we could find, and maybe, if we were lucky (which we often were), we’d walk out with a free plastic card organizer case from Phil to take home with us. I still have mine. Thanks, Phil.

"Ahem,” you interject. “I think you mean it’s how fiat money works.” Actually, no. Non-fiat money — that is, money backed by rare metals like gold — is not really so different: although fiat money can be produced ad infinitum whereas gold is finite, gold is valued mainly because, worldwide and throughout history, various large swathes of the human race have decided it should be. Value is, at the end of the day, whatever humans think it is.

Even though I have fewer remaining than he does.

Your card printing reminded me of the diamonds business.