A view from the Pinnacle

What expected value can tell us about the best sportsbooks, and some speculation about what's coming next for sports betting.

Within the world of football (soccer) betting, Pinnacle’s reputation reigns supreme. No other bookie comes close. There are entire products devoted to alerting sports bettors when Pinnacle’s lines move, so they can get ahead of the changes and place more advantageous bets on other sportsbooks.

Dissecting how football betting works could take up an entire book (and has), so I won’t go into undue detail here. But the basic contours are as follows:

Sportsbooks, or bookies, create betting markets for many sports events, the most prominent of which are the “moneyline” odds — that is, bets on which team will win a given match or whether it will end in a draw.

The odds represent the reciprocal of the probability of an outcome occurring.1 In short, this means that if Pinnacle has West Ham at 6.50 odds to beat Manchester City away, then sports bettors should expect West Ham to win about 15% of the time (1 / 6.50). And if West Ham do win, a $1 bet on them would return $6.50 to the bettor, inclusive of the $1 originally staked.

Pinnacle is widely reputed to have the “sharpest” (most accurate) odds of any football bookie out there.

This presents an opportunity. Pinnacle is just one of many, many sportsbooks where an aspiring bettor can place bets. If a “soft” bookie like Ladbrokes is offering better odds (a.k.a. a higher payout) for the same outcome — say, 7.00 — then a sports bettor should take that bet.

This may seem odd (no pun intended): 6.50 or 7.00 odds indicate a 15% or 14% probability of success, respectively. Why should you place a bet that both bookies agree is extremely unlikely to succeed?

The answer lies in expected value, or EV. In short, the expected value — your predicted ROI — on your Ladbrokes bet at 7.00 odds is nearly 8% (7.00 / 6.50). So even if you’re unlikely to win this specific bet in isolation, over time and given enough similar opportunities you’ll come out ahead overall.

You may notice a vulnerability here. The concept of expected value relies on the existence of a “ground truth” — a baseline against which expected value can be derived. Obviously it is not possible to know the outcome of a match before it occurs.2 But historically, Pinnacle’s odds have come closest. (In the example above, “ground truth” is represented by the ~15% probability implied by Pinnacle’s 6.50 odds for West Ham.3)

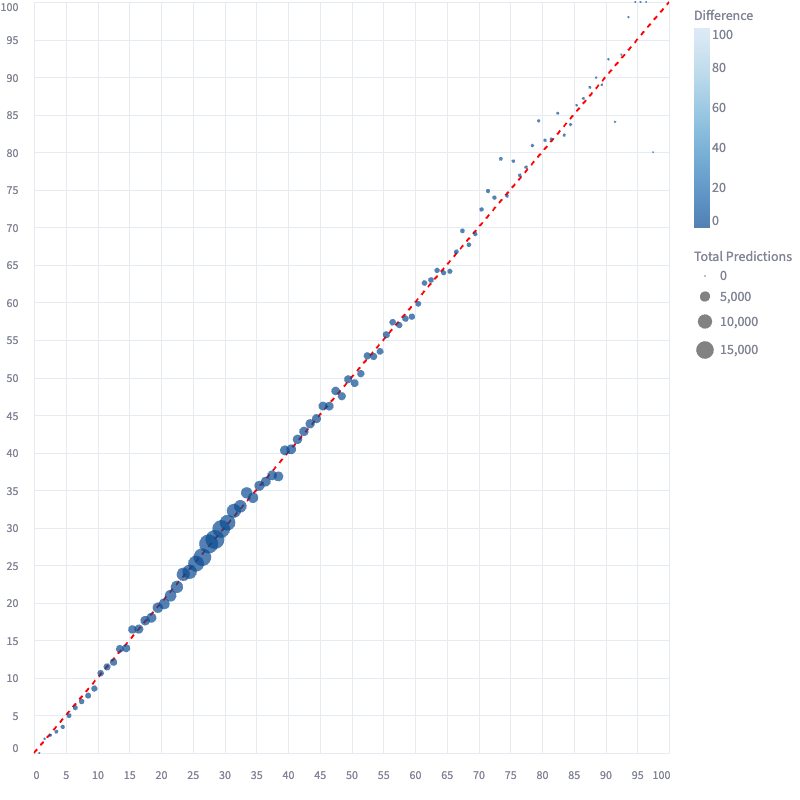

This alignment between A) the inferred predictions made by bookies and B) the actual distributions of the matches they predicted is called calibration.

So if a bookie’s historical odds (or ground truth) don’t closely approximate reality — that is, if the bookie’s odds are not well-calibrated — your expected value calculation will fail too, and you’re likely to lose money on your bets. For example, if you compiled every match outcome where Pinnacle set 6.50 odds (implying a ~15% probability), and it turned out that those outcomes happened only 10% of the time, you’d have lost money betting on those outcomes.

In Pinnacle’s case, their closing odds are well-calibrated:

As you can probably surmise, the potential risk of one’s “ground truth” metric gradually detaching from reality over time makes continuous back-testing very important. Pinnacle has been one of the most accurate bookies for a very long time, but that’s not a law of physics. Organizations change, regulatory environments shift, and sharp bettors can find other places to go.

So is Pinnacle uh, still at the pinnacle?

I developed a web app called “Bookie Accuracy” to find out. (Naming things isn’t my strong suit.) Check it out and let me know what you think! All the graphs you see in this post came from the site and are publicly available and reproducible.

Courtesy of Joseph Buchdahl’s excellent statistical resource football-data.co.uk, my “Bookie Accuracy” web site contains the pre-closing and closing odds from nearly 20 bookies for all football seasons from 2000/2001 through the current season (2025/2026) across 22 European football leagues — covering a total of 193,803 matches and 1,970,653 sets of home/draw/away (1X2) odds.4

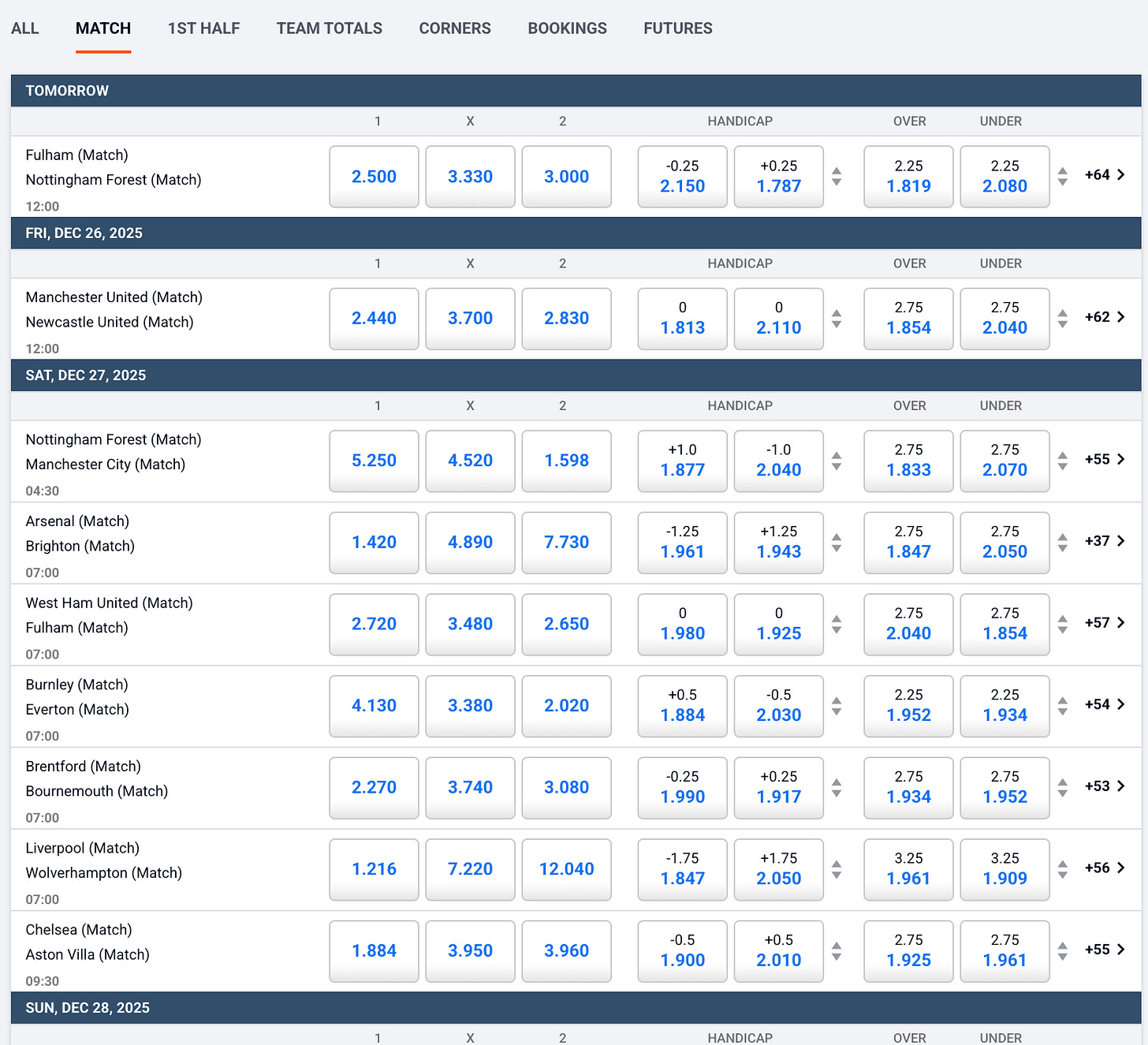

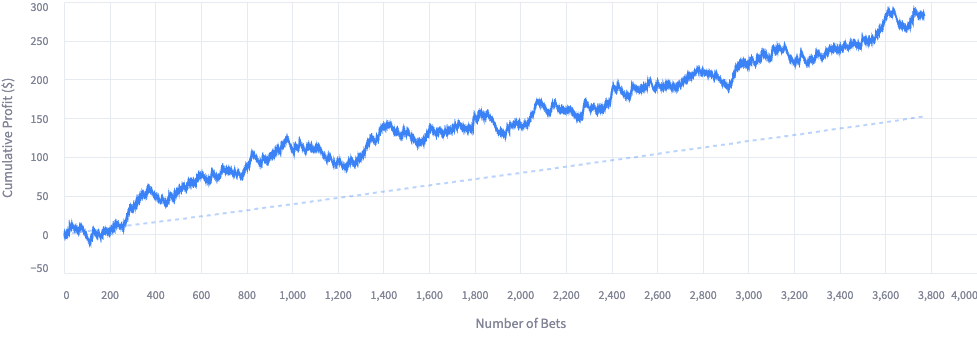

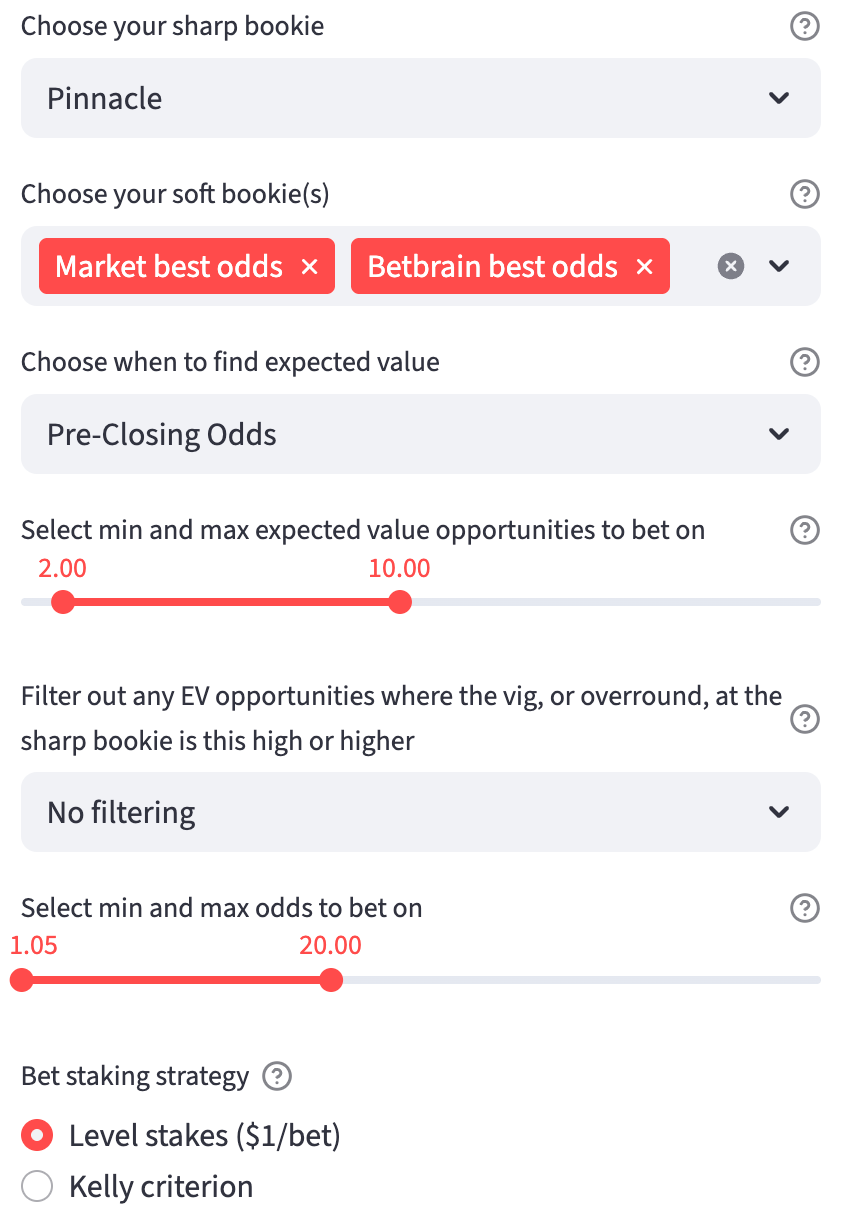

If you look at pre-closing odds5 from the 2012/2013 season onward, Pinnacle’s performance (relative to the best odds available at any other bookie in Buchdahl’s dataset at the same time) looks pretty damn good6:

That is, over a 14-season period covering 31,247 expected-value bets and assuming level betting stakes of $1 on each one, we would have expected a $1,176.72 profit (the dotted line) for a 3.8% ROI — from betting on other, “soft” bookies when they list more attractive odds than Pinnacle’s “true” odds. And in reality we’d have netted a very similar $1,117.56 (a 3.6% ROI). So using Pinnacle’s pre-closing odds as the “ground truth” over this long period in Europe’s 22 main leagues would have produced a profitable strategy.

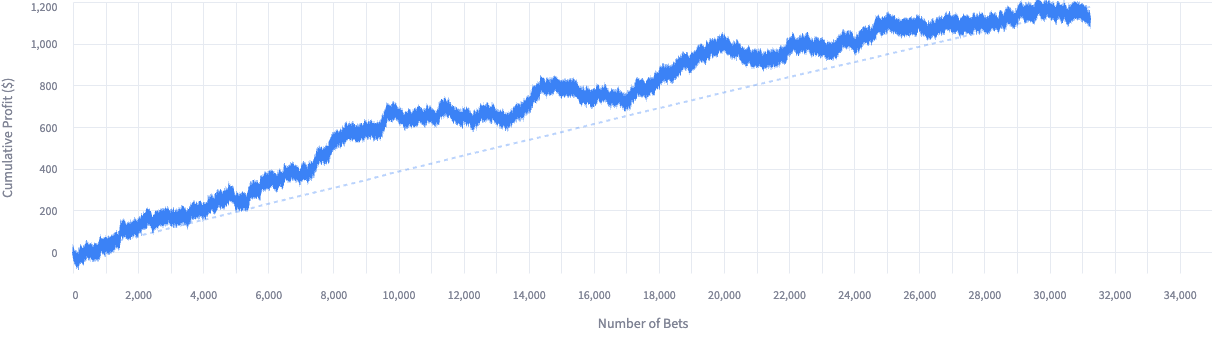

Meanwhile, Buchdahl’s dataset only has the market best closing odds for the 2019/2020 season onward7, so (aside from any other factors) this partially explains the lower EV bet volume of 23,418 using Pinnacle closing odds. The ROI here is 3.5%, below the expected 4.3% — as you can see below:

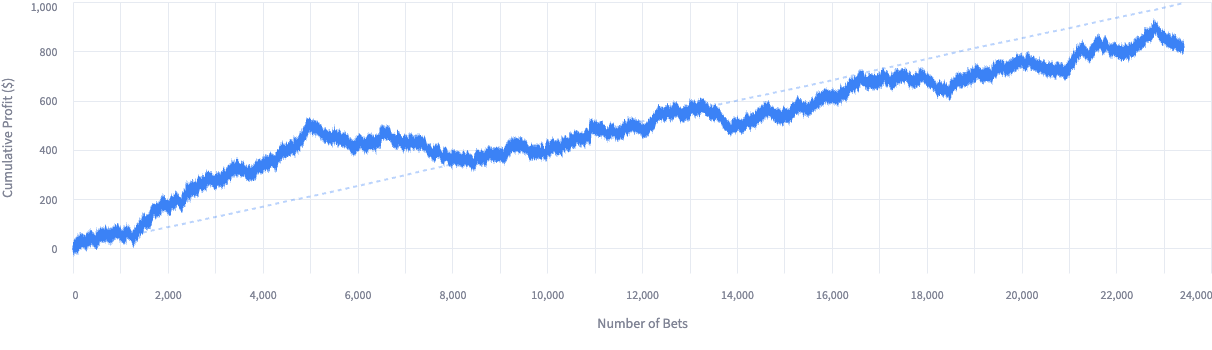

What’s interesting here is you can really spot a point where things started to fall off-track a bit, right around the 17,000th EV bet or so within that time period. In fact, if I filter EV bets against Pinnacle closing odds to only the 2023/2024 season onward, I get this much worse-looking result:

That’s a 1.9% ROI on 6,806 EV bets, against an expected 4.2% ROI — over double what happened in reality. In other words, since sometime a little over 2 years ago, Pinnacle’s closing odds no longer act as a reliable predictor of true match outcomes in Europe’s main leagues.

There are a few possible explanations for this. One is luck: in the grand scheme of things, even placing nearly 7,000 bets isn’t necessarily enough to distinguish signal from noise when the expected ROI is a mere 4.2%. Another reason was covered in a Buchdahl post and revolves around arbitrage bettors forcing Pinnacle to move its closing odds in a suboptimal direction even if its own models would have dictated otherwise.

Or, of course, Pinnacle could be losing its touch.

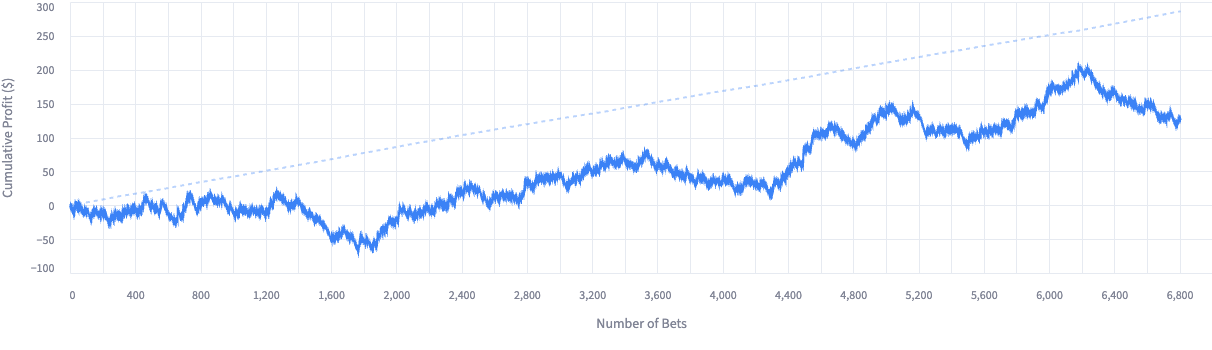

These numbers jump around a bit depending on which seasons and leagues you include. For example, if you take only the closing odds from the English Championship League and Leagues 1 and 2 from the 2000/2001 season onward, you get a significant over-performance relative to expectations: $281.87 profit (7.5% ROI) versus the predicted $152.29 (4.0%):

Is that over-performance just dumb luck, or are the baseline (Pinnacle) closing odds for these matches themselves systematically underestimating these outcomes’ probabilities? Answering that would require doing a bit more math, but suffice to say, you’d have made money even if you’d placed your bets at Pinnacle for these outcomes, never mind the “soft” bookies offering better odds.

So what’s coming next?

In a world where peer-to-peer prediction markets like Polymarket and Kalshi are increasingly becoming sports exchanges of their own, how (if at all) does this change how and where sharps place their bets?

Well, what are sharp bettors looking for in a platform? I believe it’s 3 main things:

Low vig (or overround, a.k.a. the bookie’s take)

No bans

No bet limits

Let’s go through each of those one by one.

Low vig is pretty self-explanatory. A truly elite sports bettor is still generally pulling only low single-digit percentage profit most of the time. A vig of 5% would more than likely wipe out that bettor’s entire edge.

Advantage: Prediction markets. There is no vig (technically) on these new prediction markets: you’re not actually betting against the house at all.8 Every bet you make is being matched one-for-one by someone else taking the opposite side. Polymarket and Kalshi are exchanges, not bookies. The reason I wrote “technically” there isn’t a vig is that, like any financial market with an order book, there’s a spread, which for all intents and purposes operates as a sort of vig. The less liquidity/volume, the larger the spread or “effective vig.”

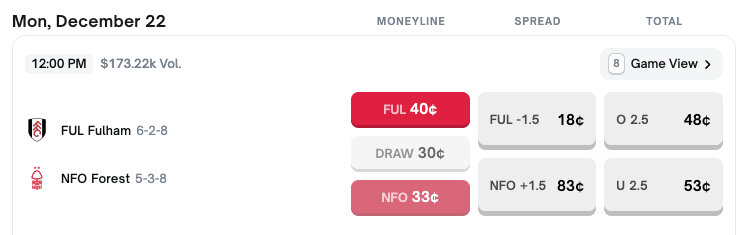

You can see this in the above example on Polymarket. Betting across all 3 outcomes would cost you $1.03 to win $1, so there’s still an effective “vig” of ~3% before you even get into questions of bet sizing. (As of the time of writing, the order book for this match is actually surprisingly deep: you could place over $45,000 of bets on each outcome at these current prices.)

What does “no bans” mean? This deserves its own separate post, but the simplest way to think about it is that bookies are best divided into two buckets: “sharp” bookies like Pinnacle, and “soft” (or “retail”) bookies like, well, almost everyone else.

Somewhat counterintuitively, the “soft” bookies’ business models are not centered around having the most accurate odds. They are about finding the most profitable bettors (as in, the ones who lose a lot of bets but keep betting anyway) — which, by implication, also means protecting themselves from the least profitable ones (a.k.a. the sharp bettors, or “sharps”).

One of the key ways these bookies achieve that latter part is by outright banning bettors who exhibit sharp behavior: again, this gets very complex but the gist is that, the more you win, the likelier you are to get banned at a soft bookie. This makes sharp bettors’ lives very complicated: the more great EV opportunities they find at soft bookies, the likelier they are to get banned for their success.

So this is absolutely an advantage for the prediction markets. They’re not putting their own money at risk — again, you’re betting against (nominal) peers, not the house — so why would they ban you for winning?

And finally, “no bet limits” is the companion to “No bans.” A bet limit is effectively a softer version of a ban: instead of kicking you off their web site or app entirely for being a sharp bettor, a “soft” sportsbook may only allow you to bet relatively small amounts on any given match, in order to limit their exposure.

Well, here’s where the incumbents like Pinnacle may still have a chance against the prediction markets. Polymarket and Kalshi won’t technically limit your betting, but you are de facto limited by the available liquidity for any given match. If you want to bet $10,000 on West Ham at 6.50 odds but there aren’t enough counterparties willing to take the other side, then you’re effectively limited to betting a smaller amount. (Relatedly, this also means the “effective vig” at your preferred stake is probably quite high.) This is where Pinnacle shines: they’re generally willing to take your bets at high volume.

This creates a bit of a chicken-and-egg scenario. Bettors have a couple good reasons to move from Pinnacle to prediction markets: no vig (sort of) and no bans. But a lot hinges on liquidity: if it isn’t there, what’s the point of moving over? And yet if no one moves over, there will never be enough liquidity.

The experience of betting exchanges is instructive here. While prediction markets are relatively new entrants into the world of sports betting, the idea of peer-to-peer sports bets is very old, and such exchanges (like Betfair Exchange) have been around for a long time. But for a variety of reasons they’ve never managed to dislodge Pinnacle.

Will Polymarket and Kalshi look more like Betfair Exchange? Or will a mass exodus of sharps from Pinnacle ensue? And who will serve as the new “ground truth” then?

The odds offered by a bookie can be expressed in decimal, fractional, or American (“moneyline”) style. I’m using decimal exclusively here.

Except in the NBA, in some circumstances.

I’m intentionally keeping things simple here. In reality, one cannot simply invert the Pinnacle odds to obtain the true probability. All bookies’ odds include a built-in vig (or overround), which has to be removed (in industry parlance, the odds need to be “devigged”) in order to reverse-engineer the true probabilities they imply. But Pinnacle doesn’t disclose how this vig is calculated (nor does any other bookie), so various methodologies are used to approximate it. Discussion of this is outside the scope of this piece, but Buchdahl’s Monte Carlo or Bust has extensive analysis. For this piece I’ve used the “constant exponent” devigging method.

If you have trouble reproducing any of my analysis here using Buchdahl’s dataset, hit me up! It is far likelier that I’ve made a mistake than that Buchdahl — who’s been collecting data for many years — has.

Joseph Buchdahl’s excellent football-data.co.uk, which is the source of all the odds and outcomes data in this post and on my web app, defines how he collects “pre-closing” odds thusly: “Betting odds for weekend games are collected Friday afternoons, and on Tuesday afternoons for midweek games.”

Odds provided by all the bookies are constantly shifting from the moment a “moneyline” market opens until just before kickoff. (In fact, most bookies allow in-match betting too, but that’s beyond the scope of this newsletter.) The general rule of thumb is that closing odds — that is, the last odds available just before the match starts — are the most accurate representation of the true probabilities of match outcomes, because they have incorporated all available information (e.g. injury reports, leaks from training sessions, managers’ interviews, etc.) up to that point.

Pre-closing odds theoretically include any odds from before that point. However, while Buchdahl’s dataset doesn’t contain precise timestamps for these, the crucial point is that all of the pre-closing odds for a given match were collected at approximately the same time, meaning that any expected value derived from pre-closing odds should represent an actual opportunity a bettor would have had at the time.

This is an artifact of where these odds are sourced. Odds comparison web site Betbrain has only pre-closing odds in Buchdahl’s dataset (going back to the 2005/2006 season), whereas Oddsportal is used only from the 2019/2020 season onward and includes both pre-closing and closing odds. So all of the Pinnacle closing odds data referenced in this post is for the period from 2019/2020 onward only.

That said, Kalshi does have fees. Polymarket doesn’t (yet). And there is also some controversy (the scope of which is beyond this piece) around whether Kalshi’s associated market maker, Kalshi Trading, has special privileges. A recent lawsuit bluntly stated that “Kalshi Trading is not a peer; it is the House.”