Too satisfied to fail

The digital advertising ecosystem is opaque, commoditized, and teeming with suspicious and fraudulent actors. It's also probably not a bubble.

(Disclaimer: this newsletter represents my own views and not those of the advertising industry at large or my employer.)

Does online advertising work?

In the process of introducing this fundamental question, Tim Hwang quickly ends up asking a narrower and more provocative one: is online advertising a bubble?

Subprime Attention Crisis: Advertising and the Time Bomb at the Heart of the Internet, clocking in at a slim 141 pages (epilogue compris), is Hwang’s attempt at answering it. His central thesis is that the digital advertising ecosystem is the heir apparent to the world of financial derivatives, specifically the type whose cascading failures edged the global economy to the brink of collapse in 2008.

Hwang is certainly not the first to notice the similarities between the twin universes of finance and programmatic advertising, nor will he be the last. However, his historical treatment of how both financial and digital advertising markets commoditized over time is a notable contribution.

For Hwang, commodification begins with standardization: it was only once the Chicago Board of Trade forged a consensus from disparate notions of grain quality that the market exploded in size and geographical reach. Similarly, a prerequisite for the rapid expansion of programmatic advertising was the digital ad ecosystem’s ability to settle on a tradable unit of human attention, the impression.

Completion of this step unlocks the second: abstraction. Once commoditized, both grain and human attention are free-floating economic units, effectively disembodied from their origins: when you buy a grain-based product at the supermarket, you neither know nor care exactly which farm produced it. It’s just…grain.

In concert, these two processes enable the formation of enormous, sometimes global markets in which countless buyers and sellers, all of whom may be strangers to each other, buy and sell units of largely undifferentiated products.

Hwang is at his best when elucidating the eerie parallels between the opaque, frothy subprime mortgage market of the early 2000s and that of the digital ad ecosystem circa 2020 — often exemplified by the explosion of ad fraud, the stampede towards semi-transparent private marketplaces (PMPs), the onset of audience ‘banner blindness,’ and the proliferation of ad tech middlemen that’s resulted in absurdist graphics like this:

If anything, Hwang goes too easy on online advertising’s startling opacity. Just one of many additional examples he could have mentioned: the practice of billing off of partners’ numbers. A pre-bid vendor — whether that’s an audience provider, contextual targeter, brand safety solution, or something else entirely — is generally forced to rely entirely on the demand-side platform (DSP) they’ve partnered with to accurately report the usage numbers — impressions, most commonly — that form the basis of their revenue-sharing agreements.

This is like launching a credit card company and calling up each of your customers at the end of the month to ask them how much they've spent, so you can bill them the right amount. There’s a reason no credit card company does this. And yet there are digital ad tech companies whose entire business models rest on these foundations.

Hwang is similarly spot-on about many industry participants’ lack of curiosity when presented with evidence of underperformance. His description of an advertising conference in which a professor argued that online behavioral targeting data was garbage will ring true for anyone who’s ever encountered apathetic shrugs while wondering aloud about various aspects of ad tech effectiveness:

I start looking around to try to gauge audience reactions, expecting to see headshakes of disapproval or at least some skeptical eyebrows. Nothing. The session wraps up, and Nico asks if there are any questions. In a conference hall of hundreds of marketers, not one hand goes up.

“Was this mere indifference, a lack of understanding,” Hwang wonders, “or a sign of something deeper and more pervasive within the industry?”

Hwang rightly marvels at the sheer volume of wasted ad budget on non-viewable inventory: “A staggering number of those ads are never seen by anyone at all.” But he falters slightly in his assessment of ad blocking, which he cites as an example of the advertising market failing to correctly price a worthless asset: an ad that was blocked before it could ever load.

In most cases, however, the publisher’s ad tags are blocked first, meaning that the blocked ad doesn’t get incorrectly priced: it doesn’t get priced at all, because an impression was never generated in the first place. (The book’s claim that “$21.8 billion in global ad revenue is lost each year to ad blockers” originates from a methodologically dubious study that does not account for dynamic pricing stemming from lower supply: ceteris paribus, ad blocking leads to a decrease in supply that should increase the relative value of all other impressions, not reduce them.)

But it is in Hwang’s persistent attachment to the finance allegory where his argument begins to stumble.

The first problem is one of size. The global digital advertising business is currently about $333 billion annually. In Q2 of 2008, the cumulative outstanding value of household mortgages in just the United States was $10.6 trillion. In fact, the value of outstanding American subprime mortgages alone was $1.3 trillion in early 2007, “nearly as large as [the] entire California economy.” American household wealth in 2008 fell by almost 34 times the entire 2020 global digital ad market.

This presents an obstacle for Hwang’s thesis, which is based on the concept that a shock to the digital advertising ecosystem — much like the one that afflicted the subprime mortgage market — has the potential to spiral out of control and into the broader economy. He bases this on the fact that advertising giants subsidize a much broader set of seemingly unrelated businesses, such as news organizations and other media properties, email, navigation, cloud storage services, and even moonshot efforts like self-driving vehicles.

This is all true as far as it goes. But the size of the industry necessarily limits the extent of any hypothetical fallout.

More problematic is the question of whether digital advertising itself is overvalued relative to other ad formats. Hwang notes that, in a bubble, the perceived value of the underlying assets begins to diverge ever more from reality. This is clearly what happened with subprime mortgages: the available supply of high-quality, low-risk mortgages turned out to be a drastically smaller portion of all mortgages than investors believed (and ratings agencies claimed).

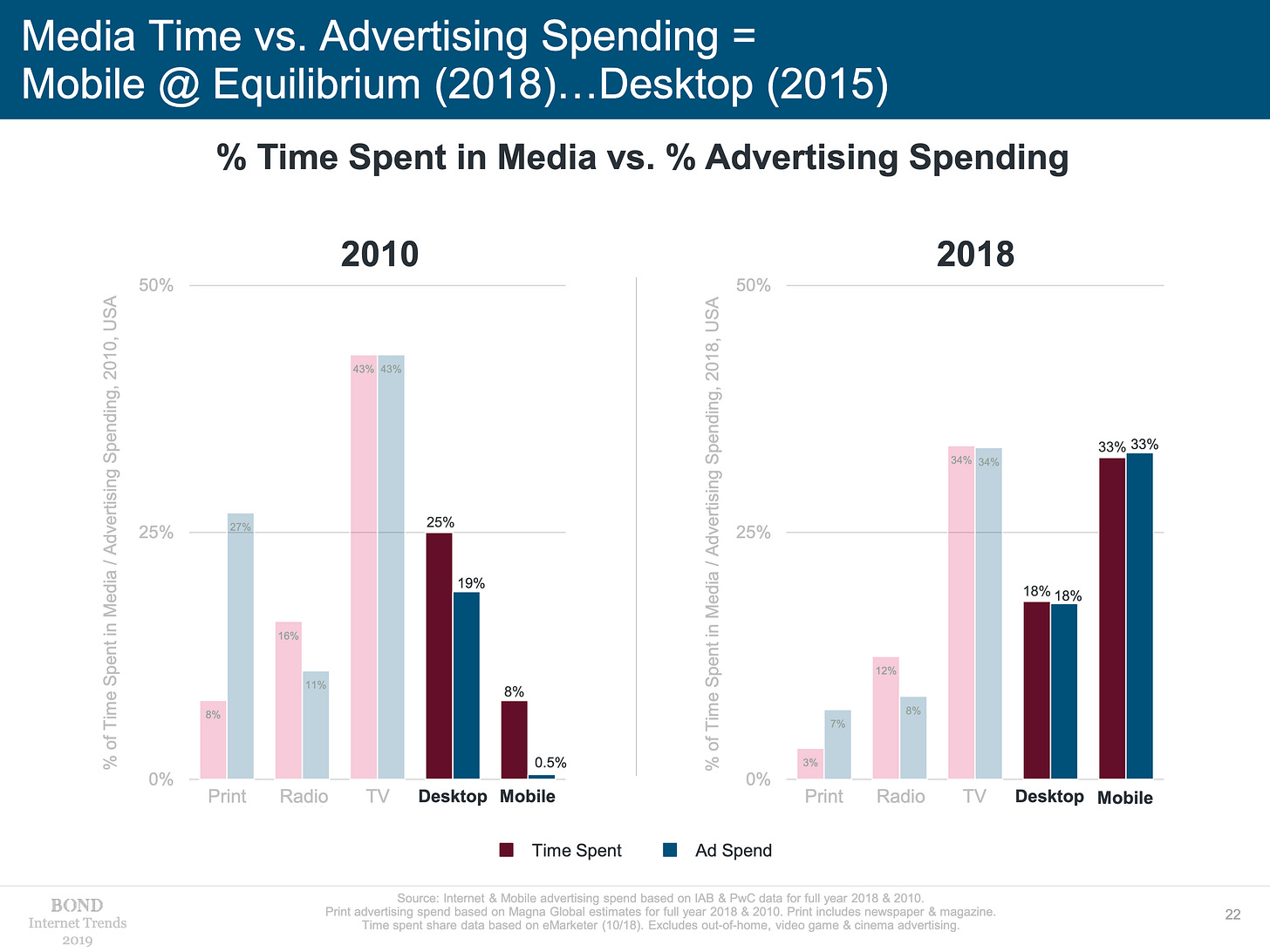

But if the digital advertising industry is, as Hwang describes, primarily a market for human attention, then the case for a bubble is tenuous. This is because the allocation of digital ad spend is actually uncannily well-calibrated with attention:

Now one could, perhaps, argue that the usage increase in digital media does not necessarily correlate to a proportional rise in the consumption of advertising. Every hour spent watching Netflix is an hour of attention that advertisers can’t touch. But to the extent that that’s true, it applies to other formats as well: podcast apps make it easy for users to skip 30-second ad pods, and TV ad breaks are the universal signal to run to the toilet or put on a kettle of tea.

And unlike the market for mortgages — which led to a bubble because the volume of high-quality loans was much lower than understood — the amount of human attention devoted to digital consumption is actually rising:

In other words, if digital ad tech is a bubble, then so is advertising everywhere else.

And maybe it is! A new academic study on television advertising published this August found that “TV advertising is about 15 to 20 times less effective than the literature said,” concluding:

However, the vast majority of brands over-invest in advertising and could increase profits by reducing their advertising spending.

…Our results reveal that even using one of the best and most widely used data sources, advertising effects are either hard to measure or the size and direction of the effects is not always as expected. We hope this work will encourage firms to re-evaluate their advertising strategies and researchers and firms to invest in data and techniques that can improve the measurement of TV advertising effectiveness.

The authors’ lament on the difficulty of measuring TV ad effectiveness echoes Hwang’s citation of perhaps the most axiomatic quote in advertising history, allegedly uttered by John Wanamaker over a century ago: “Half the money I spend on advertising is wasted; the trouble is I don’t know which half.”

The fact that the ad ecosystem of today confronts similar evergreen challenges to the ones that once bedevilled a nineteenth-century Philadelphia retailer, however, cuts precisely against Hwang’s linkage of advertising and finance (emphasis mine):

The incentive to overvalue mortgage-backed securities laid the groundwork for a larger crisis, because it was impossible to hide the underlying weakness of these assets indefinitely.

But, as we see above, it’s actually quite easy to hide the underlying weaknesses in advertising, and has been for over a hundred years, if you’re uninterested in looking for them. Hwang briefly concedes this point:

Pre-internet advertising was highly limited in the metrics that were available about performance…People wanted to buy ads, even in an information-poor environment.

In short, back in 2008 there were actual victims of the financial crisis, and no way to pretend they didn’t exist: real people couldn’t afford their mortgage payments. Their homes were foreclosed on. They were evicted. They went bankrupt. They lost their jobs.

Subprime advertising, by contrast, if not a victimless crime, is at the very least a quasi-unknowable one: the opportunity costs of subprime advertising are all counterfactuals, after all. What would you spend your advertising budget on if not advertising? This is not a question that most CMOs are eager for their bosses to answer (although some have already started to). The ultimate victims of subprime advertising are marketers’ shareholders, who are likely about as well-versed in the plumbing of digital advertising as they are in the precise ingredients of their preferred company’s soft drink or laundry detergent.

None of this is to say that advertising doesn’t work. A potential bubble doesn’t mean a market’s underlying assets are worthless: it means they’re worth less. Even the study mentioned above acknowledges that advertising has an impact. But like the mortgage market, there are good and bad products in digital ad tech and not enough clear delineation between the two.

In this respect, it is perfectly reasonable to wonder if a certain level of built-in fraud is endemic to the entire project of modern capitalism, not simply within the tiny sliver of it occupied by online advertising. Throwing up his hands at the explosion of digital ad fraud, Hwang begs his readers to picture a real-world equivalent:

Imagine a supermarket with the level of inventory fraud that exists in the programmatic marketplace. In some aisles, one out of every five products on the shelves is a fake: you’d return home to find that these boxes contain nothing. Even when you stick to familiar brands that you recognize and trust — a six-pack of Coca-Cola or a box of Wheaties — your purchases turn out to be imitations filled with sawdust. You’d probably stop going to this supermarket, even if you did occasionally manage to get some of the groceries you wanted.

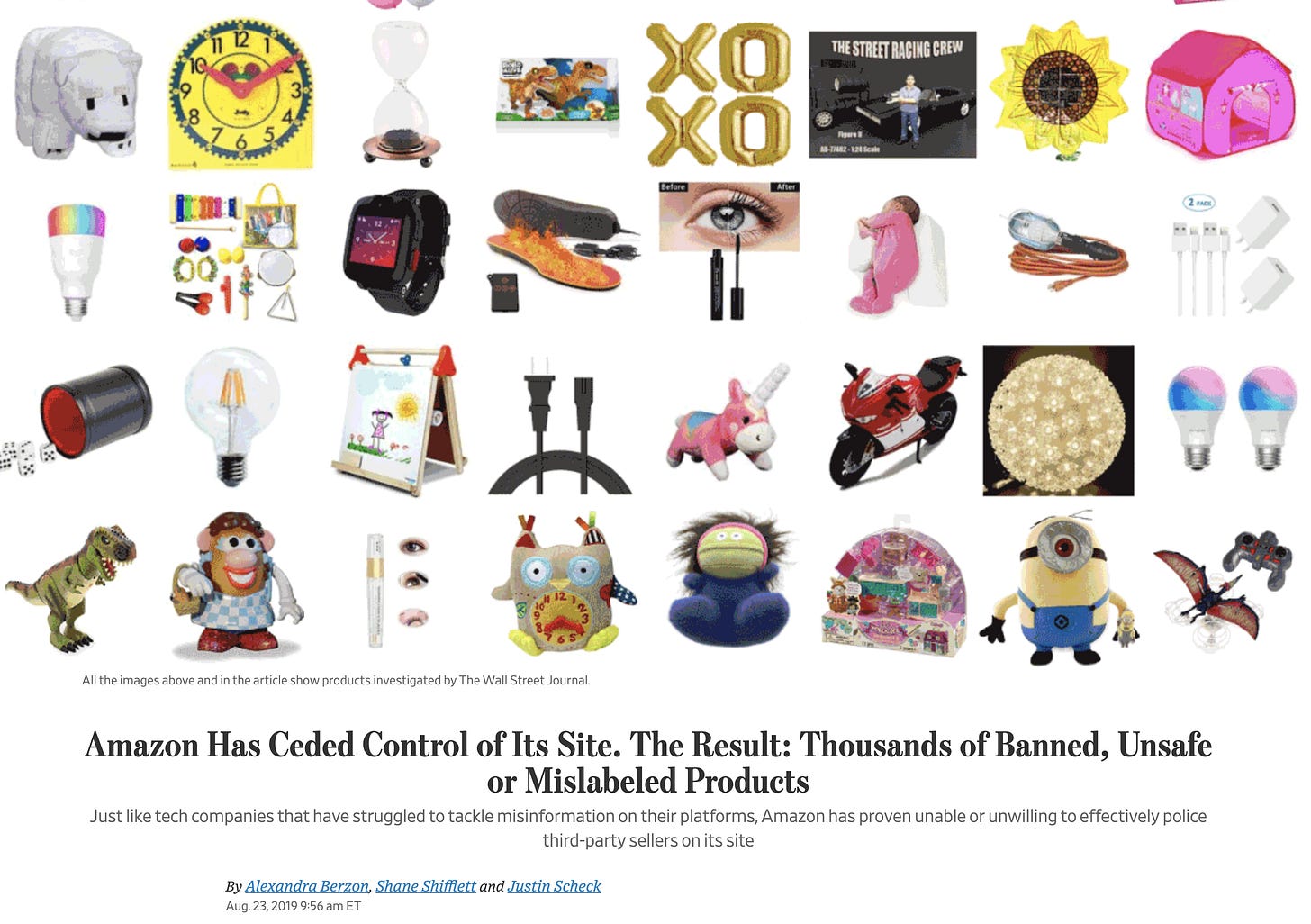

But such a supermarket already exists, and no one’s stopped going at all: to the contrary, it’s more valuable now than ever.

In short, no, it is not clear that online advertising is a bubble. But one can forgive Tim Hwang for thinking it is. His fault lies not in being overly pessimistic, but rather the reverse: in order to pop a bubble, you first need a market that’s curious enough to poke around.