The case for democracy

Democrats aren't just fighting Republicans on policy. They're battling an elaborate Jim Crow electoral regime that spans all three branches of government and threatens voters everywhere.

So, how bad is it?

Tonight, on the eve of Election Day, here’s a sobering thought: someone born in 1989 is now 31 years old and has lived through only a single election (2004) in which a Republican presidential candidate won more votes than the Democrat. Nevertheless, a Republican has occupied the White House for half of this time period. A recent study on the Electoral College found that “Republicans should be expected to win 65% of Presidential contests in which they narrowly lose the popular vote.”

In the most recent federal elections — the 2018 midterms — the Democrats romped at the polls, winning the popular vote in the House of Representatives by 8.6%, “the greatest on record for a minority party heading into an election.” And yet they won six fewer House seats than the Republicans did just two years earlier, when they won the popular vote by a mere 1.1%. (An Associated Press study found, moreover, that the Democrats would have won 16 additional House seats in 2018 were it not for gerrymandering.) In 2012, the Democrats actually won the House popular vote by 1.2% and yet lost the chamber to Republicans by a whopping 33 seats.

The last time Republicans in the Senate, meanwhile, represented more collective votes than their Democratic counterparts was two decades ago, in 2000. But they have held a majority in the Senate for 10 of the 20 years since. This is because the median American state is currently 6.6% more Republican than the nation overall. Given current population trends, 20 years from now half the country’s population will be represented by only 16 senators, while the other half are represented by more than five times that total, with 84.

In fact, the current 53-47 Republican Senate majority, representing less than half the American population, just confirmed Amy Coney Barrett as the Republicans’ sixth of nine justices on the Supreme Court. (The fifth, Brett Kavanaugh, was confirmed two years ago by a Republican Senate representing 44% of the American population.) Going back to 1969, 15 of the last 19 Supreme Court justices have been appointed by Republican presidents, who won the popular vote in fewer than half — six out of 13 — of the presidential elections covering that period.

The Republican imprint on the entire federal judiciary, extending far beyond the Supreme Court, is monumental as well: Trump alone has filled nearly a third of all seats on federal appeals courts. Republican Senate leader Mitch McConnell has made it his singular mission to stack the court system with doctrinaire movement conservatives as quickly as possible, a rush that has resulted in the nomination of alarmingly under-qualified judicial candidates like 33-year-old Kathryn Kimball Mizelle, who has practiced law for less than a decade, never tried a case, and — like nine of her fellow Trump-selected nominees for lifetime appointment — received a “not qualified” rating from the American Bar Association. (None of Obama’s judicial nominees received this rating over his two terms.)

It’s bad enough that every major institution in our national American political system — the presidency, the House, the Senate, and the Supreme Court — is profoundly anti-democratic. What makes it worse is that, as demonstrated above, these biases pile on top of each other: Republican presidents who lost the popular vote nominate Supreme Court justices and other federal judges to lifelong tenure, who are then confirmed by a Senate representing a minority of the country. (And — contra the theatrical GOP alarm about the possibility of Democrats packing the Supreme Court — it’s Republicans who have added seats to state supreme courts in recent years when they haven’t gotten their way.)

But the coup de grâce is what happens next: this skewed judiciary has brought the hammer down on voting rights, election oversight, and democratic reform in case after case, shrinking the effective electorate and protecting partisan Republican interests, completing an infinite loop that ultimately facilitates the long-term stacking of a right-wing judiciary that’s wildly out of step with the American public.

This pattern is particularly evident at the high priesthood of American jurisprudence: the U.S. Supreme Court, now far afield of its midcentury role as protector of the disenfranchised, is the one doing much of the disenfranchising.

The Republican assault on voting

Making it harder to vote is a well-documented, foundational tenet of the Republican Party’s political orthodoxy.

Per The New York Times, Republicans in the crucial swing state of Pennsylvania have implemented “a three-pronged strategy that would effectively suppress mail-in votes,” using tactics like videotaping ballot drop boxes and fast-tracking legal appeals to tighten voting restrictions.

Politico, citing Republican voter suppression efforts in Pennsylvania, Nevada, Ohio, New Hampshire, and Arizona, concluded: “Never before in modern presidential politics has a candidate been so reliant on wide-scale efforts to depress the vote as Trump.” The former general counsel for late Republican senator John McCain acknowledged: “There just has been this unrelenting Republican attack on making it easier to vote.” Mitt Romney’s chief strategist from his 2012 presidential run was similarly withering: “They’re not even pretending not to rely on voter suppression.”

The Washington Post reports that Republicans “have shifted their legal strategy in recent days to focus on tactics aimed at challenging ballots one by one, in some cases seeking to discard votes already cast during a swell of early voting.”

The Republican governor of Texas this year capped ballot drop boxes at one per county, “a measure with outsized effects on the most heavily populated — and more Democratic — areas.” Texas Republicans also challenged curbside voting in Harris County (home of Houston) in both state and federal lawsuits, asking judges to throw out more than 100,000 ballots from a disproportionately Democratic jurisdiction. (Neither one did — so far.)

In Florida, a hugely popular referendum to restore voting rights to ex-convicts was largely nullified by an effective poll tax levied by the Republican state legislature, which now blocks these prospective voters — many of whom are African American — from voting until they pay any outstanding fines. But, per CBS News, “with no one centralized system, [fine] records can be missing, conflicting, inaccurate, or scattered,” making it impossible for many to pay their fines and thus vote even when they have the requisite funds.

The U.S. Postal Service, led by a Trump donor, famously switched up its procedures in the middle of a pandemic and slowed down mail delivery nationwide (particularly in heavily African American and Democratic strongholds like Detroit), just as mail ballot deadlines are looming.

The Republican mayor of Miami-Dade County blocked his hometown NBA team, the Miami Heat, from opening their stadium to the public as a voting center — despite the fact that 19 other NBA teams did so.

Republican state attorneys general even went so far as to try to prevent Facebook from promoting voter registrations this year.

When all else fails, Republicans persistently — and incorrectly — decry the voting process itself as rife with fraud, an accusation belied by copious evidence to the contrary. (One representative study’s finding: “It is more likely that an individual will be struck by lightning than that he will impersonate another voter at the polls.”)

Even legendary Republican election attorney Benjamin Ginsberg, who practiced election law for nearly four decades, admitted defeat in a recent op-ed:

The truth is that after decades of looking for illegal voting, there’s no proof of widespread fraud. At most, there are isolated incidents — by both Democrats and Republicans. Elections are not rigged.

He expounded on Republican voter suppression efforts in a new piece published just yesterday:

This is as un-American as it gets. It returns the Republican Party to the bad old days of “voter suppression” that landed it under a court order to stop such tactics — an order lifted before this election. It puts the party on the wrong side of demographic changes in this country that threaten to make the GOP a permanent minority…

Trump has enlisted a compliant Republican Party in this shameful effort. The Trump campaign and Republican entities engaged in more than 40 voting and ballot court cases around the country this year. In exactly none — zero — are they trying to make it easier for citizens to vote. In many, they are seeking to erect barriers.

Despite the dearth of evidence for voter fraud, in September a New York Times Magazine investigation documented “an extensive effort to gain partisan advantage by aggressively promoting the false claim that voter fraud is a pervasive problem,” explaining:

This story did not originate with Trump. It has its roots in Reconstruction-era efforts to suppress the votes of newly freed slaves and came roaring back to life after the passage of the Voting Rights Act…”

It is nothing short of a decades-long disinformation campaign — sloppy, cynical and brazen, but often quite effective — carried out by a consistent cast of characters with a consistent story line.

The examples are endless, but the principle is quite succinct: the Republican assault on the ability of citizens to vote is comprehensive and all-consuming.

All of this would be bad enough on its own. But the judicial branch has repeatedly translated this authoritarian, anti-democratic streak of the Republican Party into the law of the land, rubber-stamping Republican-led voting restrictions, decimating campaign finance regulation, and effectively reestablishing a Jim Crow regime targeted at voting blocs likely to vote Democratic and designed to cement Republican minority rule.

In recent years, much of the damage inflicted on voting rights by Republican states, and then blessed with the imprimatur of the federal judiciary, arrived as a direct consequence of Chief Justice John Roberts’ 2013 gutting of the Voting Rights Act, civil rights-era legislation that had given the federal government “preclearance” authority to bar (primarily southern) states with a history of voter suppression from making changes to their election procedures. Roberts found that these covered jurisdictions were outdated and thus unfairly targeted by the law: “The Fifteenth Amendment is not designed to punish for the past; its purpose is to ensure a better future.”

To which the late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, in a rejoinder for the ages, replied: “Throwing out preclearance when it has worked and is continuing to work to stop discriminatory changes is like throwing away your umbrella in a rainstorm because you are not getting wet.”

Ginsburg would be vindicated soon enough. The consequences of Roberts’ decision were immediate:

Within 24 hours of the ruling, Texas announced that it would implement a strict photo ID law. Two other states, Mississippi and Alabama, also began to enforce photo ID laws that had previously been barred because of federal preclearance.

The umbrella was gone. The rainstorm stayed.

The comprehensive list of cases demonstrating courts’ antipathy to democracy in recent years is far too long to list here. But a Supreme Court reform group, Take Back the Court, just released a study of election-related judicial decisions in federal courts that revealed that “Republican appointees interpreted the law in a way that impeded ballot access 80 percent of the time, versus 37 percent for Democratic ones.” (The GOP figure rose to 83% for judges appointed by Trump.) And just days ago, a new Washington Post analysis reached virtually the same result:

…Nearly three out of four opinions issued in federal voting-related cases by judges picked by the president were in favor of maintaining limits. That is a sharp contrast with judges nominated by President Barack Obama, whose decisions backed such limits 17 percent of the time.

The impact of Trump’s court picks could be seen most starkly at the appellate level, where 21 out of the 25 opinions issued by the president’s nominees were against loosening voting rules.

Several of the dizzying array of recent election-related decisions (many of them prompted by voting challenges stemming from the pandemic) emit more than a faint whiff of impropriety. The above-mentioned Florida legislature’s poll tax on ex-felons, for example, was initially blocked from implementation by a district court. But that decision was subsequently reversed by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit last month, in a 6-4 vote in which five Trump-nominated judges were in the majority. Florida is, of course, a critical state in Trump’s narrow path to reelection.

Similarly, the one-drop-box-per-county rule implemented by the Texas governor — another hotly contested presidential election state — was also first blocked by a district court judge, but was then unanimously upheld on appeal by three Trump-nominated judges in the Fifth Circuit, who wrote that actual evidence of voter fraud “has never been required to justify a state’s prophylactic measures to decrease occasions for vote fraud or to increase the uniformity and predictability of election administration.”

In a Wisconsin voting case that was just decided in Republicans’ favor in the U.S. Supreme Court last week, Justice Brett Kavanaugh wrote a concurring opinion that appeared to lend credence to Trump’s baseless claims that ballots counted after Election Day may somehow be illegitimate. (As The New York Times reported, his opinion “misconstrues the voting process, where official results often are not fully tabulated for days or even weeks after an election.”) His slipshod opinion was so riddled with misleading analogies and outright factual errors that he was compelled to issue a rare correction following an official complaint from Vermont’s Secretary of State.

This wasn’t the only concerning turn of events in the nation’s highest court in just the last few days. Last Wednesday, an opinion joined by three Supreme Court justices left open the possibility that some late-arriving ballots in Pennsylvania may be thrown out, despite the Pennsylvania Supreme Court’s ruling to the contrary. (The Supreme Court, except in very rare cases, doesn’t typically interfere in state supreme court rulings that are based on that state’s own constitution.)

But perhaps no decision was as brazen as the Eighth Circuit’s ruling just this past Thursday, in which a 2-1 majority (which included one of Trump’s ten nominees rated “not qualified” by the ABA) blocked yet another district court ruling — issued by a Trump-nominated judge, no less — that had allowed Minnesota to count ballots received up to a week after Election Day, per a bipartisan consent decree between the Secretary of State and a voting rights group. (The plaintiffs are Republican presidential electors who will vote for Trump in the Electoral College if he carries the state.)

This decision not only ignored issues of standing and grossly violated the “Purcell principle” guiding courts against late changes to election procedures, but it also threatened to throw Minnesota’s election into chaos: with only five days between the court decision and Election Day, voters who had intended to mail in their ballots under the rules enacted months earlier now faced the prospect of having them thrown out due to their late arrival (an outcome made likelier by the aforementioned USPS slowdown). Senator Amy Klobuchar (D-MN) and others rushed to inform voters that it was now too late to mail in their ballots:

Election law professor Rick Hasen was appalled: “It's no exaggeration to say yesterday's 8th Circuit ruling was the single worst piece of judging over election disputes this entire cycle.”

Even Washington Post reporter Amy Gardner was taken aback by the chutzpah of the Republican case:

Trump, meanwhile, has repeatedly and publicly propagated his view of the Supreme Court — and especially its newest member, Amy Coney Barrett — as a protective firewall ensuring his reelection:

The fix is in. A minority-elected president, in collaboration with a minority-elected Senate, has — in a single term — installed three Supreme Court justices who have then presided over a sprawling court system whose collective finger rests ever heavier on the scale for the Republican Party.

Why is it so important to fix this?

So that’s the bad news. But what does it all mean for American democracy?

Let’s start with the obvious: this system is grossly unfair to Democrats and, therefore, to the types of people who vote Democratic — city-dwellers, for example, and, ahem, people who believe in the scientific consensus on climate change.

Our anti-democratic system incentivizes political behavior from elected Republicans that’s utterly divorced from the American public’s policy preferences. As political forecaster Nate Silver pointed out in a recent interview:

[The Republican skew in the Senate and Electoral College] has a couple of implications. One is that you have public policy catered to an older, more rural, whiter electorate. The GOP does not take advantage of that by saying, we’re going to win every election for all of eternity — we can have a stable, majoritarian coalition. Instead, they say, we’re going to actually pass very aggressive policies that the median voter would not like. But we don’t need to win the median voter. That governs a whole lot of decisions that they make.

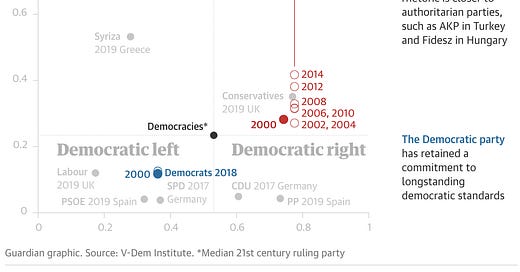

This political calculus results in various negative outcomes, some of them quite dangerous. Most nefariously, it has led elected Republicans into a vicious cycle where — either convinced they cannot win in free and fair elections, or apathetic to doing so given its apparent lack of necessity — they have grown increasingly authoritarian, feverishly opposing all efforts to expand voting and even going so far as encouraging voter intimidation. Multiple studies and datasets have documented the Republican Party’s far-right turn in recent years, fuelled in large part by “ethnic antagonism” and resulting in “adopting attitudes and tactics comparable to ruling nationalist parties in Hungary, India, Poland and Turkey.”

This democratic misalignment also manifests itself in more pedestrian ways. Take universal background checks on gun purchases. This is a policy supported by about 90% of all Americans. And yet Congress perpetually fails to pass legislation enacting it, because our cohort of national elected officials is not responsive to the majority of American voters.

And universal background checks are just the tip of the iceberg.

In fact, an enormous swathe of Democratic and progressive policy ideas are extremely popular with the public. Americans love taxing the rich. And not just their income taxes: two-thirds of Americans want to tax their wealth too. (No word yet on eating the rich. Baby steps.) Four in five Americans oppose the Supreme Court removing protections for patients with preexisting conditions. Nearly three-quarters of Americans support a $2 trillion stimulus package that Democrats have been trying (unsuccessfully) to pass in the GOP-controlled Senate. Two-thirds of Americans favor a public healthcare option. (Medicare for All actually polls above 50% too, although the survey wording makes a significant difference in support levels.) Two-thirds want a $15 federal minimum wage. Two-thirds support automatic voter registration and making Election Day a national holiday. Two-thirds are in favor of Puerto Rican statehood (and have been for decades). Six in ten Americans want to abolish the Electoral College. The same number support the reduction of fossil fuel usage. Pluralities of various sizes support restricting or eliminating the filibuster.

You get the point.

This popular legislation, and much else besides, languishes year after year. This is not only grossly unfair to the majorities or pluralities of Americans who support these policies, but it also reinforces the perverse notion that voting, and thus democracy, does not work — a long-term degradation of democratic politics that erodes the incentives for civic participation.

So (and here I tempt the gods), if tomorrow Joe Biden wins the presidency and Democrats take back the Senate (they’re virtually certain to maintain control of the House), they need to do the following, and fast:

Pass the For the People Act and the John R. Lewis Voting Rights Act to reform campaign finance, fight corruption, and expand voting rights

Add Washington, D.C. and Puerto Rico as U.S. states

Expand the Supreme Court by at least two seats

As a necessary byproduct of the aforementioned goals, they’ll have to eliminate the filibuster too: Republicans won’t go along with any of the above plans, and Democrats won’t win the necessary sixty seats to defeat a filibuster in even the wildest “blue wave” scenario.

Would eliminating the filibuster help a newly ascendant Democratic Party pass more laws? Yes, of course. But it would also force both parties to engage in more honest lawmaking:

“One of the worst things about the filibuster is it allows senators to say they support something without ever having to stand behind a vote,” says Stasha Rhodes, director of the 51 for 51 campaign, which advocates for a DC statehood vote free from the filibuster. “It’s one thing to say you support DC statehood and another to say you support bypassing the filibuster to see it actually happens. It is one thing to talk about the need to reduce gun violence in America. It’s another to say you’re going to remove the hurdles that stand in that bill’s way. The difference between removing the filibuster and not is the difference between theory and action.”

These reforms are not simply a plan to extend Democratic political power, although they would certainly do so in the short term. One of the hidden long-term benefits of pursuing such an aggressive policy of democratic reform is to put in place a framework that forces the Republican Party to confront the grim reality of its spiralling demographic base and reinvent itself in response, rather than relying on decaying, anti-majoritarian institutions like the Senate, the Electoral College, and the Supreme Court to rescue it from obsolescence. Clinging blindly to an aging, white, rural base within a diverse, urbanizing America should be a path to political irrelevance, not a highway towards white nationalism.

These moves would also, moreover, help resolve the rather straightforward conundrum Democrats face in the near term: virtually any major progressive policy they attempt to pass — no matter how popular — will be struck down by a hostile, activist judiciary. Unlike FDR’s attempts at Court-packing in the 1930s, however, the mere threat of an expanded Supreme Court is not sufficient today: the Democratic Party must follow through with it. The trifecta of unified control of the presidency, the House, and the Senate is not a prize that appears often (Democrats have enjoyed it for only two of the last 20 years), and the Supreme Court is nothing if not supremely patient. The moment the trifecta is broken — based on historical patterns, this is likely to occur in the 2022 midterms — everything of note the Democrats have passed will fall, like so many dominoes, in the courts.

The point of political power, after all, is to use it. Sometimes, like passing Obamacare during the height of its unpopularity (only to see its support skyrocket later on), being in power means doing important but unpopular things. At other times, like whatever follows Election Day 2020, it might mean saving American democracy.